Part 1. Molecular Interactions.

A. Introduction.

Molecular interactions are attractive or repulsive forces between molecules and between non-bonded atoms. Molecular interactions are important in chemistry, biochemistry and biophysics, including protein folding, drug design, pathogen detection, materials science, sensors, nanotechnology, separations, origins of life, and gecko feet. Molecular interactions are also known as noncovalent interactions, intermolecular interactions, non-bonding interactions, noncovalent forces and intermolecular forces. All of five of these phrases mean the same thing.

Non-Bonding Interactions. Molecular Interactions are between molecules, and between atoms that are not linked by bonds. Molecular interactions can be cohesive (attraction between like), adhesive (attraction between unlike) or repulsive. Molecular interactions change (and bonds remain intact) when (a) ice melts, (b) water boils, (c) carbon dioxide sublimes, (d) proteins unfold, (e) RNA unfolds, (f) DNA strands separate and (g) membranes disassemble. The enthalpy of a given molecular interaction, between two non-bonded atoms, is 1 - 10 kcal/mole (4 - 42 kjoule/mole), which in the lower limit is on the order of RT and in the upper limit is significantly less than a covalent bond.

Bonding Interactions. Bonds hold atoms together within molecules. A molecule is a group of atoms that associates strongly enough that it does not dissociate or lose structure when it interacts with its environment. At room temperature two nitrogen atoms can be bonded (N2). Bonds break and form during chemical reactions. In the chemical reaction called fire, bonds of cellulose break while bonds of carbon dioxide and water form. Bond enthalpies are on the order of 100 kcal/mole (400 kjoule/mole), which is much greater than RT at room temperature.

Boiling Points. When a molecule transitions from the liquid to the gas phase (as during boiling), ideally all molecular interactions are disrupted. Ideal gases are the ONLY systems where there are no molecular interactions (except short range repulsion during collisions). Differences in boiling temperatures give good qualitative indications of strengths of molecular interactions in the liquid phase. High boiling liquids have strong molecular interactions. The boiling point of H2O is hundreds of degrees greater than the boiling point of N2 because of stronger molecular interactions in H2O(liq) than in N2(liq).

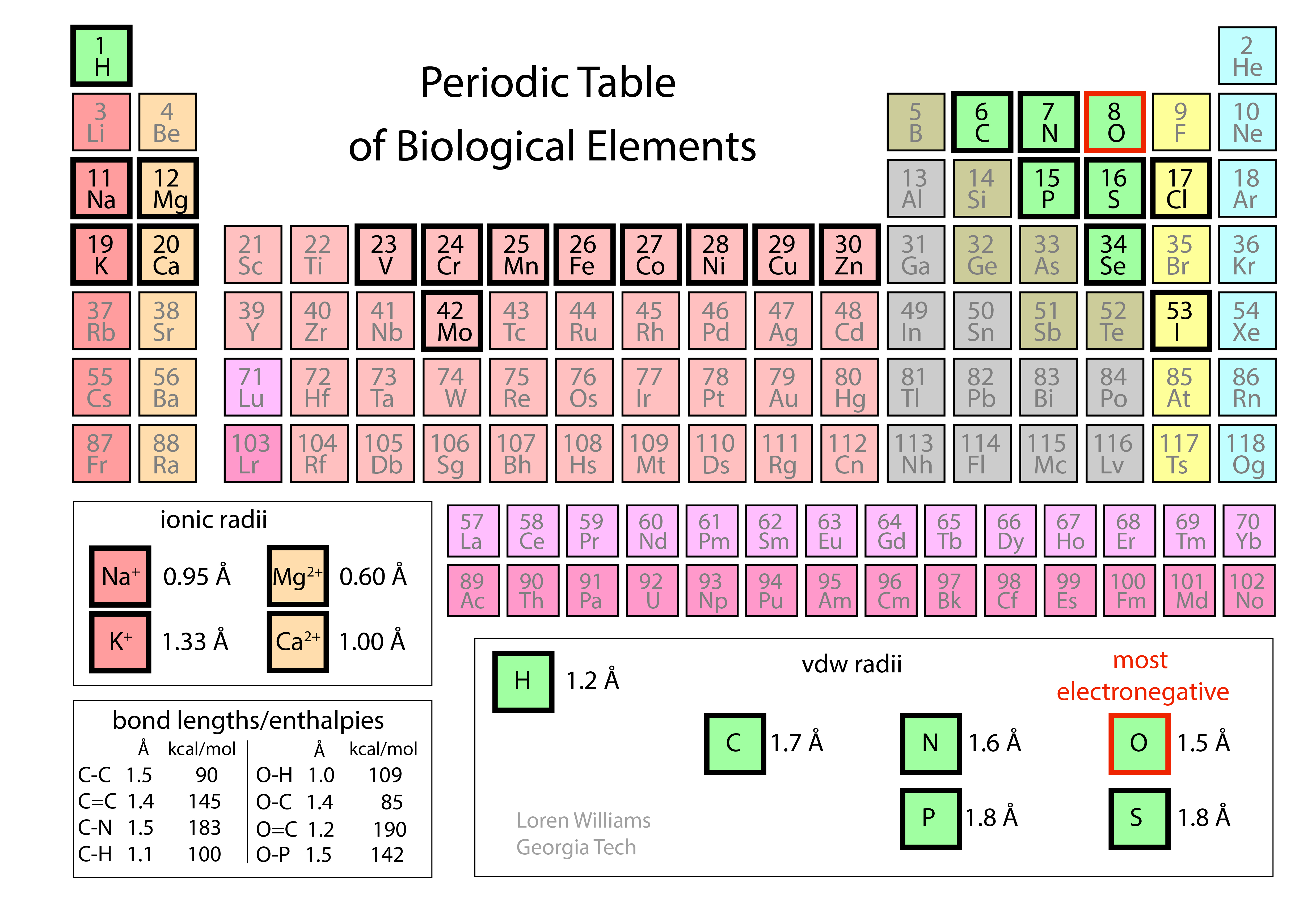

The Periodic Table. To understand molecular interactions, we need to know atomic sizes, shapes, and electronegativities. The Periodic Table summarizes this information.

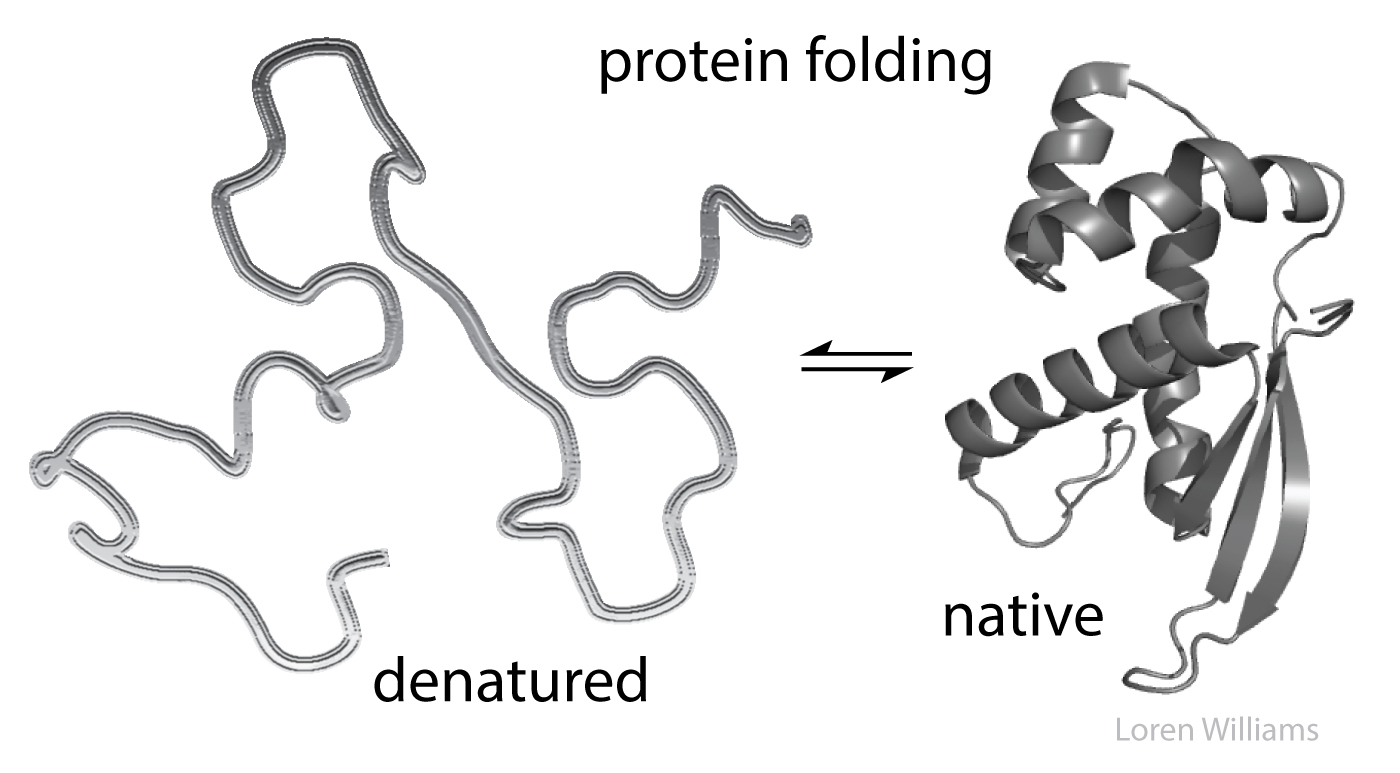

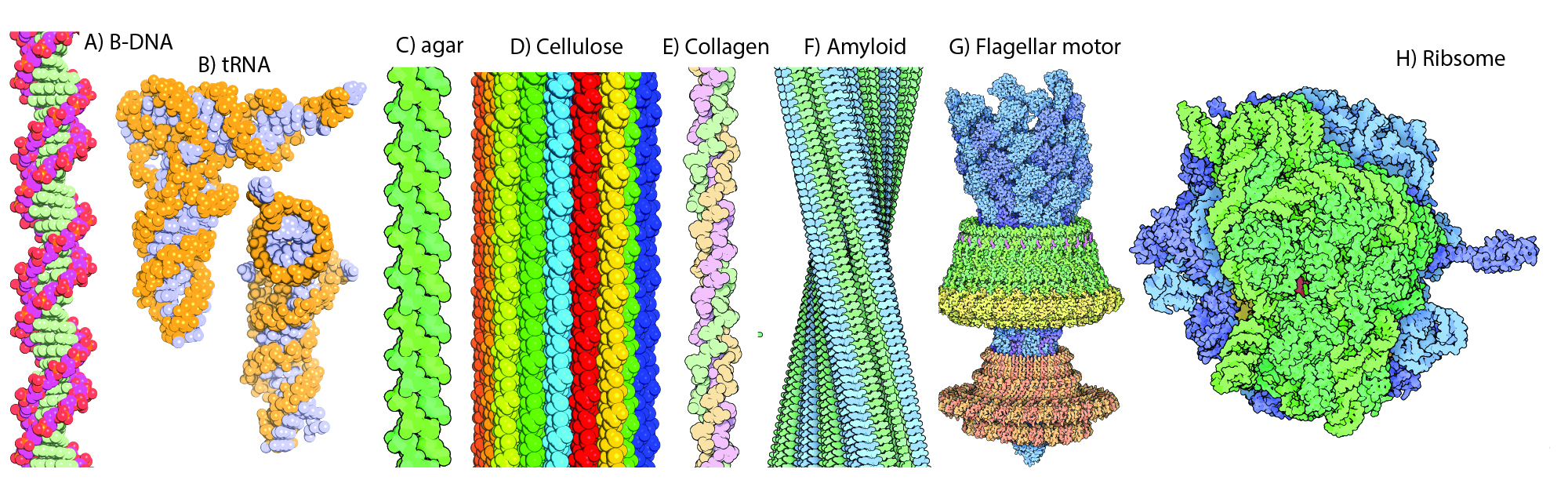

Native states. In biological systems, biopolymers assemble to form fantastic structures, called native states. These structures can be unimolecular, as when a simple protein or tRNA folds, or multimolecular, as when many strands of polyglucose assemble to form a cellulose fibril, or several large rRNAs join with many ribosomal proteins to form a ribosome.

Denatured states. When you unfold a protein or an RNA (denature them) or separate two strands of DNA (melt it), or disassemble and melt the ribosome, then interior regions become exposed to the surroundings, which are mostly water plus ions. Molecular interactions within the native state or assembly are replaced by molecular interactions with aqueous surroundings.

Monster truck tug-of-war. Biological molecules in general are pushed by powerful forces in opposing directions. Molecular interactions stabilize both folded and unfolded states. Huge numbers of intramolecular interactions within a protein native state are opposed by huge numbers of intermolecular interactions in the denatured state, with surrounding water molecules, ions, etc. On balance, native biological macromolecules and assemblies are marginally stable, near the tipping point. A small perturbation can change the balance from folded state to unfolded state. A small change in pH or temperature or a single mutation can unfold a protein.

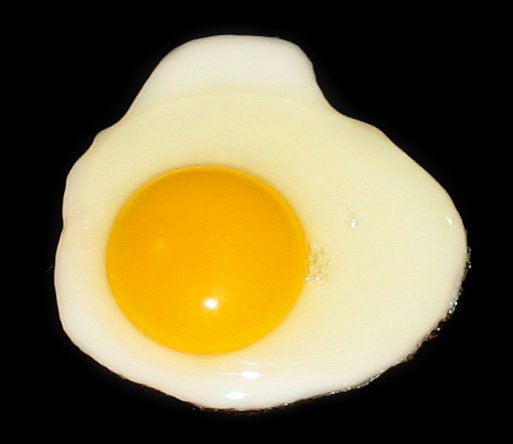

Have you ever denatured a protein (converted it from the native state to denatured state)? Yes. When you heat an egg to around 60° C, the albumin proteins denature and aggregate. You are not breaking bonds when you boil an egg - you are changing and rearranging molecular interactions. The aggregated protein forms large assemblies that scatter light, giving the egg a white appearance. When you add lemon juice to milk, the pH drops and the proteins denature and aggregate. Have you ever melted DNA? Yes, if you have run a PCR reaction.

We avoid the term "van der Waals interaction". Molecular interactions were discovered by the Dutch scientist Johannes Diderik Van der Waals. He noticed that molecules take space and are sticky, like wet jelly beans. Sadly for students, and practicing scientists too, the nomenclature relating these phenomena is a mess. Molecular interactions are also known as noncovalent or intermolecular or non-bonding or van der Waals interactions, or noncovalent or intermolecular or non-bonding forces. The term, 'van der Waals interaction' has become effectively meaningless because definitions are so inconsistent and arbitrary and because it does not describe interactions in a physically meaningful way. Even IUPAC offers several competing definitions of "van der Waals interaction", one of which arbitrarily excludes ion-diple and ion-induced dipole interactions. Terms including 'van der Waals surface' and 'van der Waals radius' are well-defined and are useful (see below).

All molecular interactions are fundamentally electrostatic in nature and can be described by some variation of Coulombs Law. However, we reserve the term 'electrostatic interaction' to describe interactions between charged species (ions). Interactions between partial charges are given other names.

There are many different ways of parsing or classifying molecular interactions. The categories in the Table of Contents are used here because they are the clearest and easiest to understand and are broadly used in the literature.

Lennard-Jones. The Lennard-Jones potential is an empirical description of molecular interactions. However, the L-J potential does not account for all molecular interactions. Electrostatic interactions are not included in the L-J potential.

Atoms take space. Force two atoms together and they will push back. When two atoms are close together, the occupied orbitals on the atom surfaces overlap, causing repulsion between surface electrons. This repulsive force between atoms acts over a very short range, but is very large when distances are short. The allowed distance between atoms depends on the type of atom and for metals, the ionization state as shown in the periodic table below.

The repulsive energy goes up as (di / R)12, where R is the distance between the atoms and di is the distance threshold below which the energy becomes repulsive. di is the vdw radius and depends on the type of atom (as shown in the periodic table above). The large exponent means that when R < di then small decreases in R cause large increases in repulsion. Short range repulsion only matters when atoms are in very close proximity (R < di), but at close range it dominates other interactions. Because this repulsion rises so sharply as distance decreases it is often useful to pretend that atoms are hard spheres, like very small pool balls, with hard surfaces (called van der Waals surfaces) and well-defined radii (called van der Waals radii).

As two atoms approach each other their van der Waals surfaces make contact when the distance between them equals the sum of their van der Waals radii. At this distance the repulsive energy skyrockets. The smallest distance between two non-bonded atoms is the sum of the van der Waals radii of the two atoms. A sulfur atom and a carbon atom can come no closer together than:

Of course we are assuming here that bonds do not form. When two atoms form a bond, they come very close together and their der Waals radii and surfaces are violated.

Short range repulsion is important to you. It prevents your hands from passing through each other when you clap, and prevents atoms from collapsing into tightly packed states of enormous density of 1014 g/ml, which is the density of condensed atomic nuclei. Very high gravity, as on neutron stars, overwhelms short range repulsion and causes atoms to collapse.

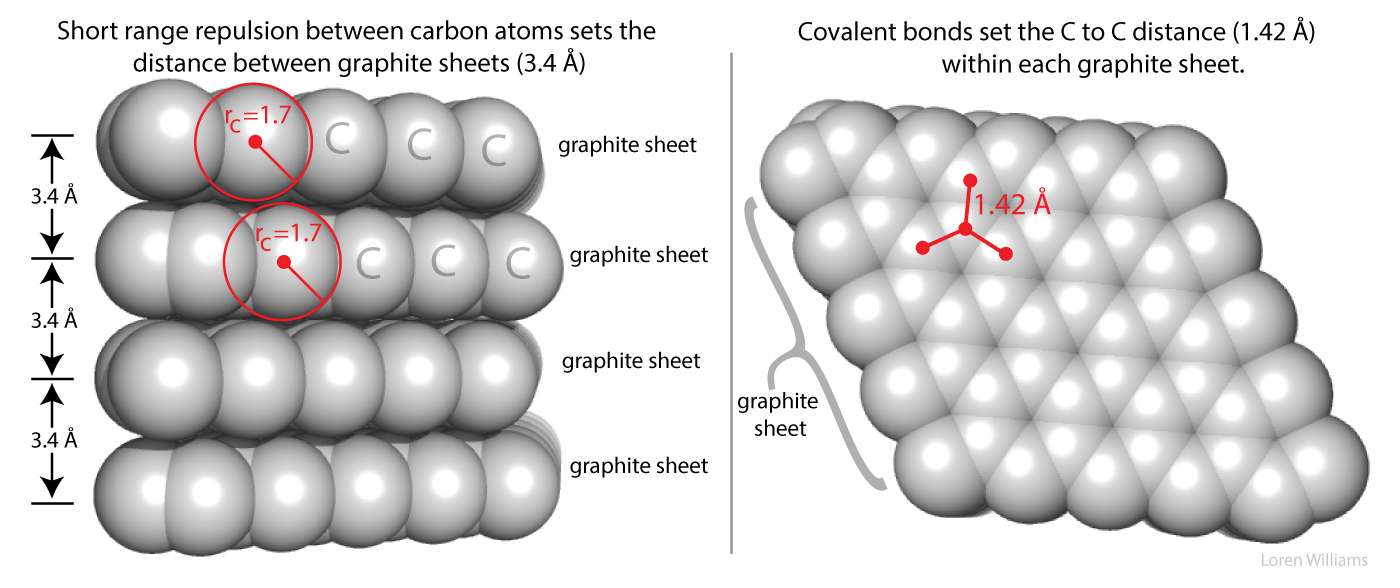

Here in earth, with our modest gravity, the van der Waals radius of carbon (rC) is evident from the spacing between the layers in graphite. The distance between atoms in different layers of graphite is never less than twice the van der Waals radius of carbon (2 x rC = 2 x 1.7 = 3.4 Å). The atoms within a graphite layer are covalently linked (bonded), which causes interpenetration of van der Waals surfaces. Carbon atoms within a layer are separated by 1.42 Å, which is much less than twice the van der Waals radius of carbon. As explained in other sections of this document vdw surfaces are also violated when molecules form hydrogen bonds. The coordinates of graphite are here [coordinates].

How do you sense short range repulsion? Try compressing a liquid.

C. Electrostatic interactions.

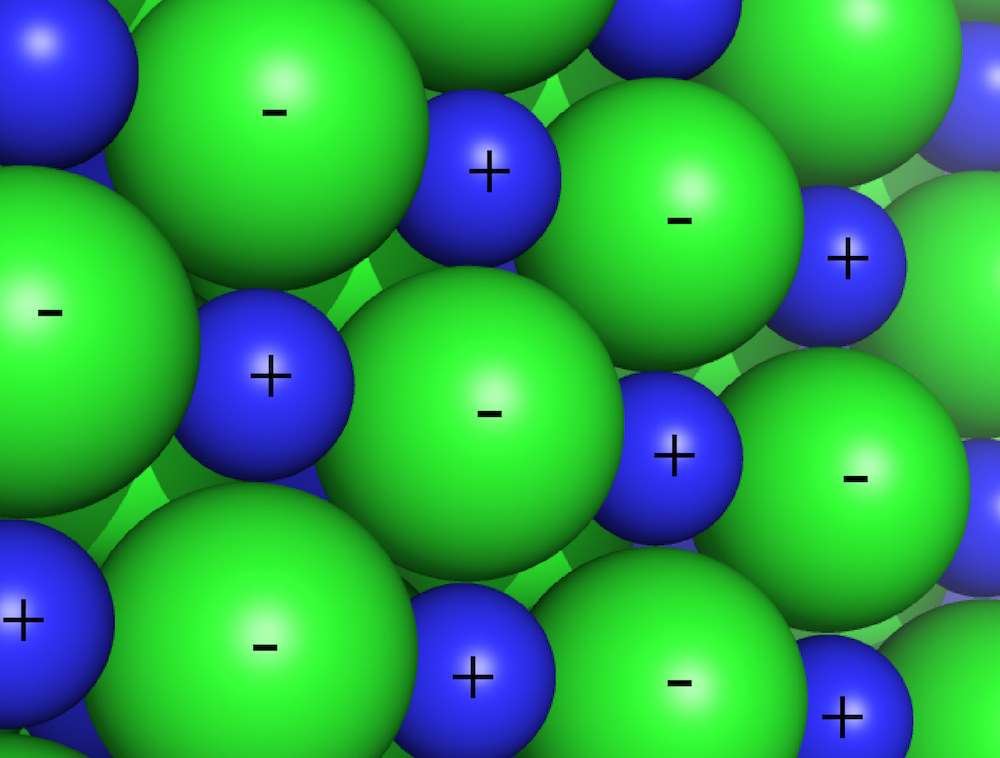

Electrostatic interactions are between and among cations and anions, species with charge of ...-2,-1,+1,+2... Electrostatic interactions can be either attractive or repulsive, depending on the signs of the charges. Like charges repel. Unlike charges attract.

Favorable electrostatic interactions cause the vapor pressure of sodium chloride and other salts to be very low. If you leave crystals of table salt (NaCl; Na+=cation, Cl-=anion) on a hot pan, how long does it take before they vaporize and sublime away? A very very long time; electrostatic interactions are very very strong. The electrostatic interactions within a sodium chloride crystal are called ionic bonds. But when a single cation and a single anion are close together, within a protein, or within a folded RNA, those interactions are considered to be non-covalent electrostatic interactions. Non-covalent electrostatic interactions can be strong, and act at long range. Electrostatic forces fall off gradually with distance (1/r2, where r is the distance between the ions).

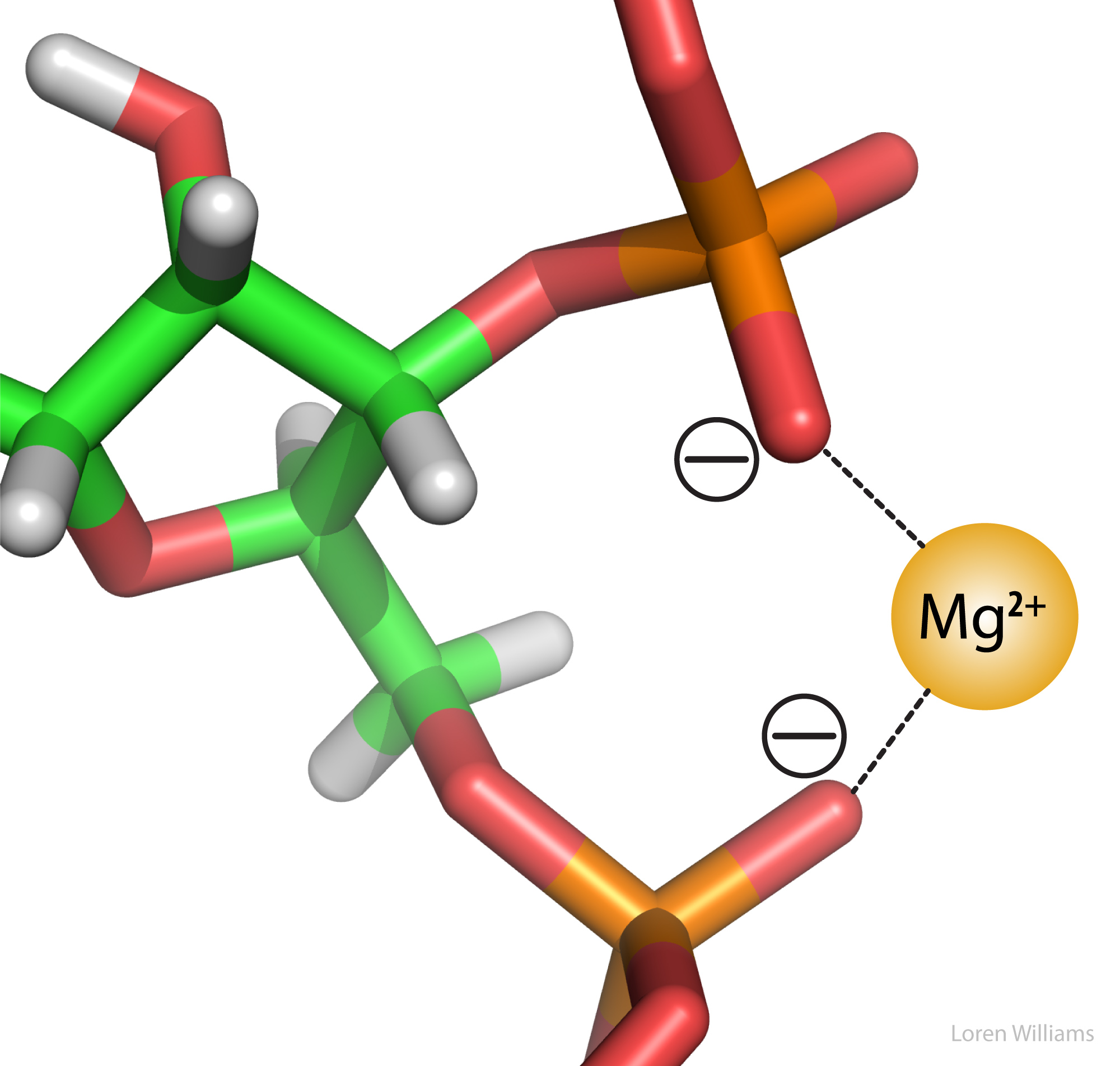

Electrostatic interactions are the primary stabilizing interaction between phosphate oxygens of RNA (charge = -1) and magnesium ions (charge = +2), as shown in the figure below. There are many magnesium ions associated with RNA and DNA in vivo. As explained later in this document, electrostatic interactions are highly attenuated (dampened) by water. In protein folding, RNA folding and DNA annealing, electrostatic interactions are dependent on salt concentration and pH.

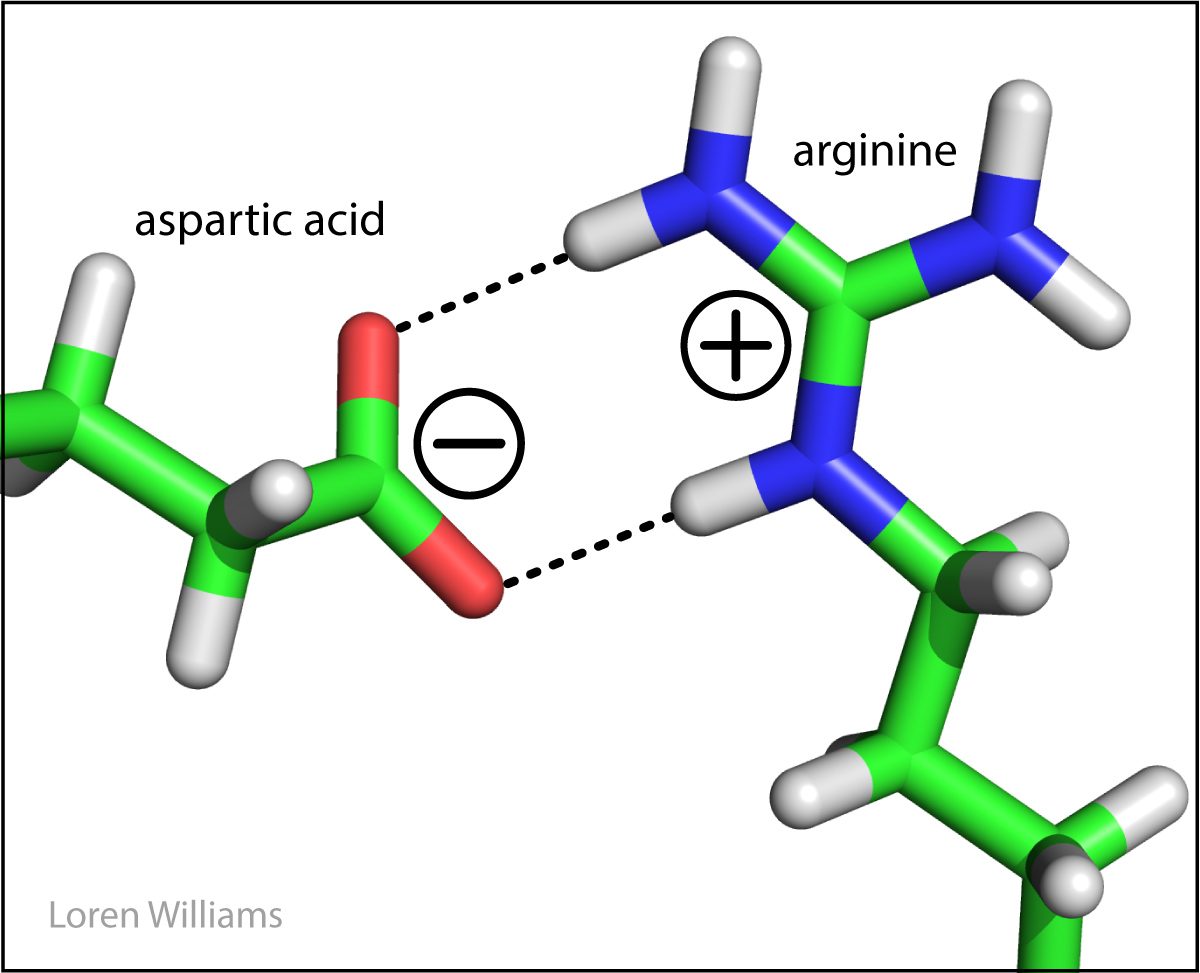

Favorable electrostatic interactions between paired anionic and cationic amino acid sidechains are reasonably frequent in proteins. Ion Pairs, sometimes called Salt Bridges, are formed when the charged group of a cationic amino acid (like lysine or arginine) is around 3.0 to 5.0 Å from the charged group of an anionic amino acid (like aspartate or glutamate). The charged groups in an ion pair are generally linked by hydrogen bonds, in addition to electrostatic interactions.

The electrostatic force between two point charges is given by:

Force = k q1 q2 / ε r2

where k = 9.0 x 109 nt-meter2 / coul2

q = -1.6 x 10-19 coulombs for an electron.

r = distance between the point charges (meters)

ε = the dielectric constant of the medium (unitless).

ε is the dielectric constant. It reflects the tendency of the medium to shield charged species from each other. ε is 1 in a vacuum, around 4 in the interior of a protein and 80 in water. Water is very efficient at shielding charges, reducing electrostatic forces between ions. The problem of calculating electrostatic effects in biological systems is complex in part because of non-uniformity of the dielectric environment. The dielectric micro-environments are complex and variable, with less shielding of charges in regions of hydrocarbon sidechains and greater shielding in regions of polar sidechains.

The electrostatic energy is given by:

ΔE= k a q1 q2 / ε r

where a = Avogadro's number.

One can crudely estimate the energetics of a charge-charge interaction in a protein. The energy of an amine (charge +1) and a carboxylic acid (charge -1) separated by 4 Å in the interior of protein is given by:

ΔE = -(9.0x109nt-m2/coul2)(6.02x1023)(1.6x10-19coul)2 /4( 4x10-10m)

= 87 kjoules/mole = 21 kcal/mole

This rough approximation is around 10-fold greater than the values determined experimentally. An ion pair contributes favorable ΔG of 1 to 4 kcal/mole (4.1 to 16.4 kjoule/mole) to the stability of a native protein.

A note on nomenclature. The attractive forces between a Mg2+ ion and phosphate groups (above) are called electrostatic interactions. Species with charge ...2,1,-1,-2... engage in electrostatic interactions. We use other terms (dipole-dipole...) to describe interactions between partial charges. The naming scheme is confusing because ALL molecular interactions are between electrons and electrons and between electrons and nuclei, and are actually electrostatic in nature. It might have been better to use different names that make more sense. However, by convention we have to restrict the term electrostatic to interactions between charged species.

| Atom | Electronegativity (unitless) |

| H | 2.2 |

| C | 2.6 |

| N | 3.0 |

| O | 3.5 |

| P | 2.2 |

| S | 2.5 |

Electronegativities. Before you can understand dipolar interactions, you have to know about electronegativity. Electrons are not shared equally in a molecule with unlike atoms. The tendency of any atom to pull electrons towards itself, and away from other atoms, is characterized by a quantity called electronegativity. Fluorine is the most electronegative atom (4.0) and cesium is the least electronegative (0.7). In general, electronegativity increases with nuclear charge while holding number of core electrons constant (i.e. from left to right in a row of the periodic table). Electronegativity increases as nuclear shielding decreases (from bottom to top in a column of the periodic table).

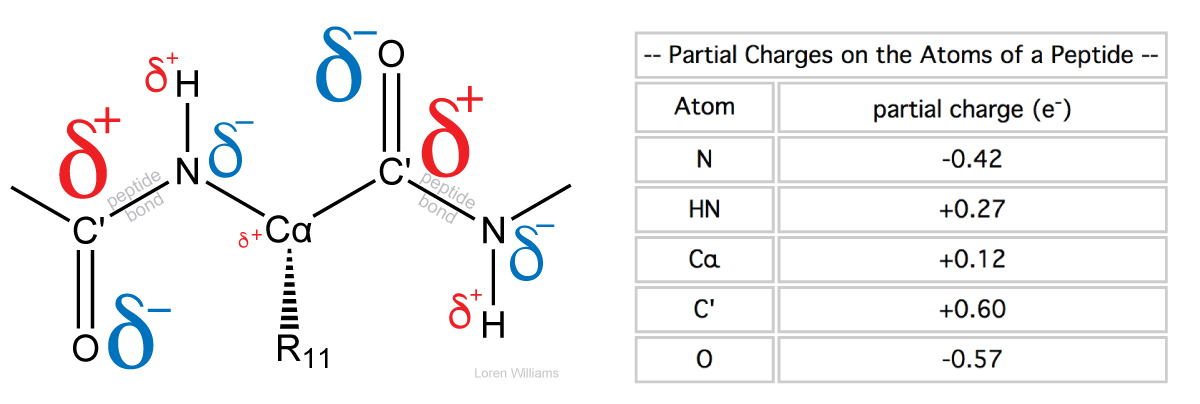

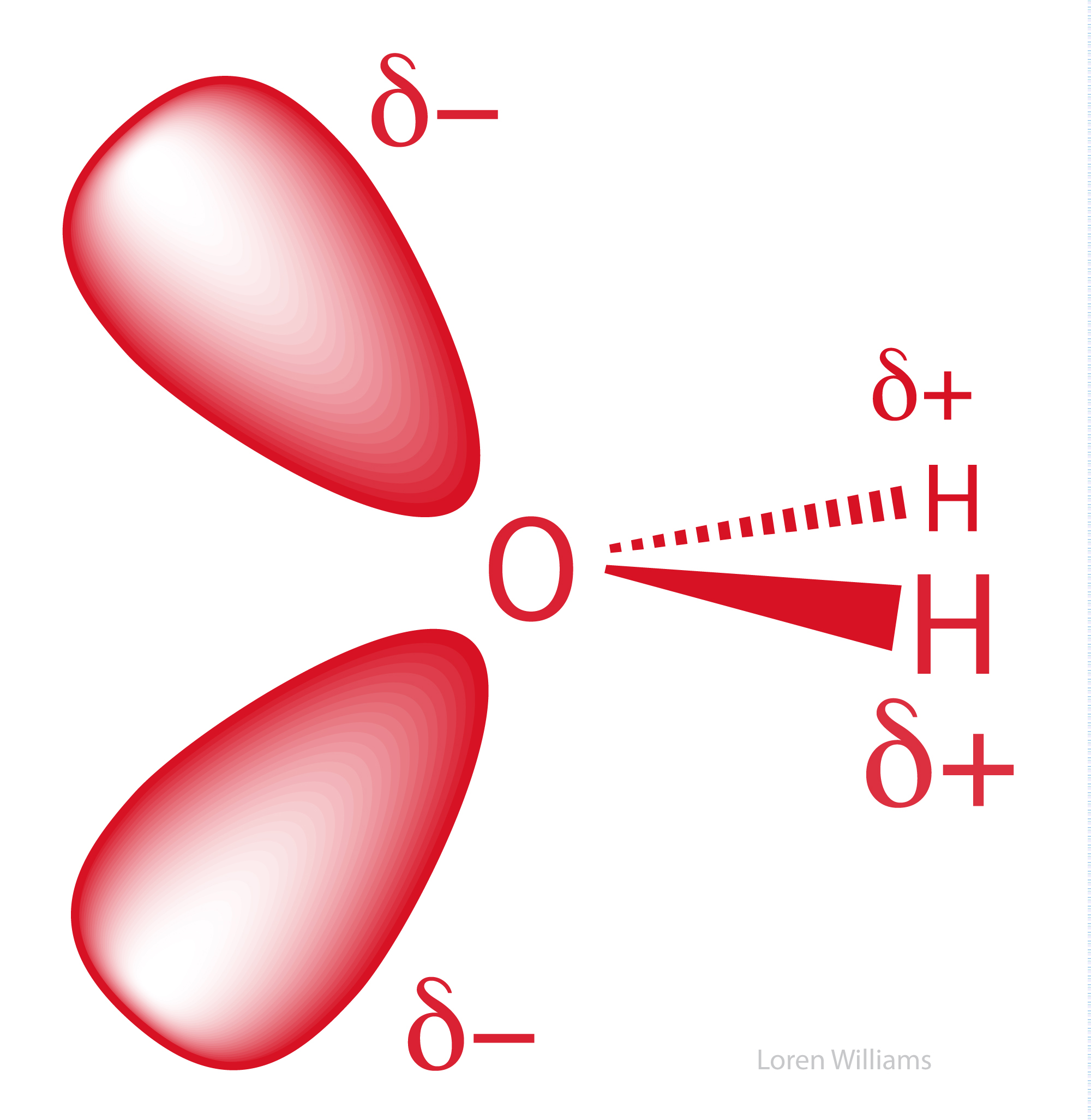

Partial Charges. In a molecule composed of atoms of various electronegativities, the atoms with lowest (smallest) electronegativities hold partial positive charges (δ+) and the atoms with the greatest electronegativities hold partial negative charges (δ-). A greater difference in the electronegativities of two bonded atoms causes the bond between them to be more polar, and the partial charges on the atoms to be larger in magnitude. In biological systems, oxygen is generally the most electronegative atom, carrying the largest partial negative charge.

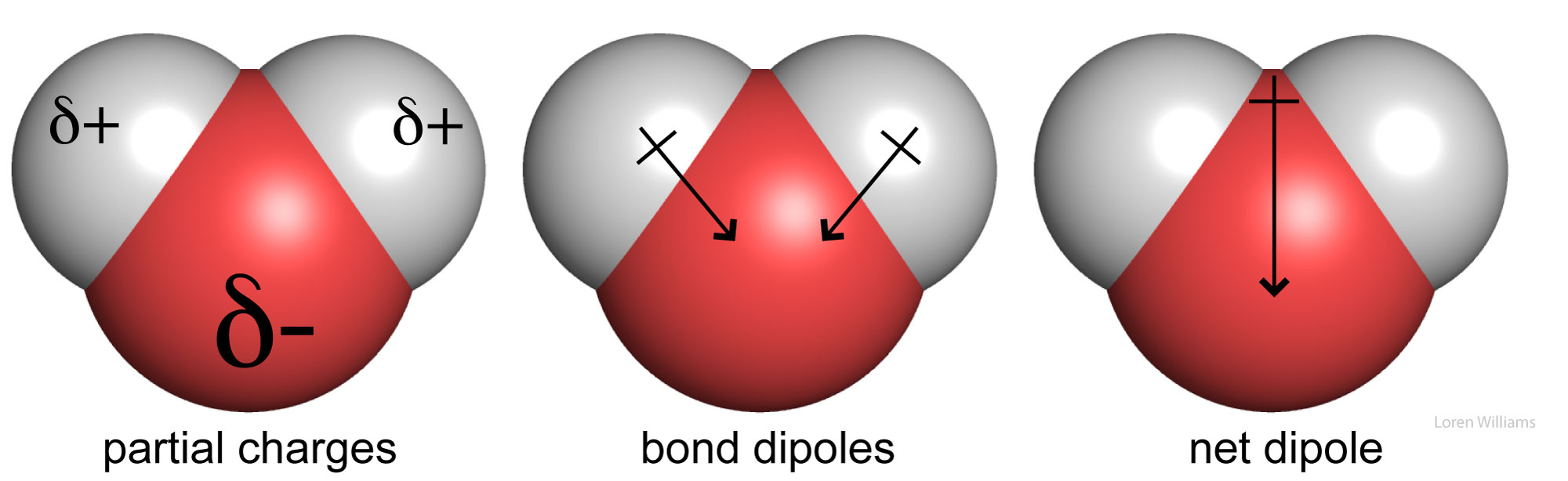

In methanol (CH3OH), the electronegative oxygen atom pulls electron density away from the carbon and hydrogen atoms. In water (H2O), the electronegative oxygen atom pulls electron density away from both hydrogen atoms. The oxygen atom of water carries a partial negative charge. The hydrogen atoms carry partial positive charges. This phenomena of charge separation is called polarity. Methanol and water are polar molecules. N2 is a non-polar molecule because the two nitrogen atoms have equal electronegativities and so they share electrons equally. Hydrocarbon (CH3CH2...CH2CH3) is non-polar because the electronegativies of carbon and hydrogen are similar.

Dipole moments. The extent of charge separation within a molecule is characterized by the dipole moment μ. A dipole moment is determined by the magnitudes of the partial charges and by the distances between them. To quantitate dipole moments, charges are expressed in esu's and distances in centimeters. The dipole moment of an electron and a proton separated by 1 Å equals:

(4.8 x 10-10 esu) (10-8cm) = 4.8 x 10-18 esu cm

= 4.8 Debye

The dipole moment of water is 1.85 Debye (HCl = 1.1 D; CH3Cl = 1.9 D; HCN = 2.9 D; NH3 = 1.47).

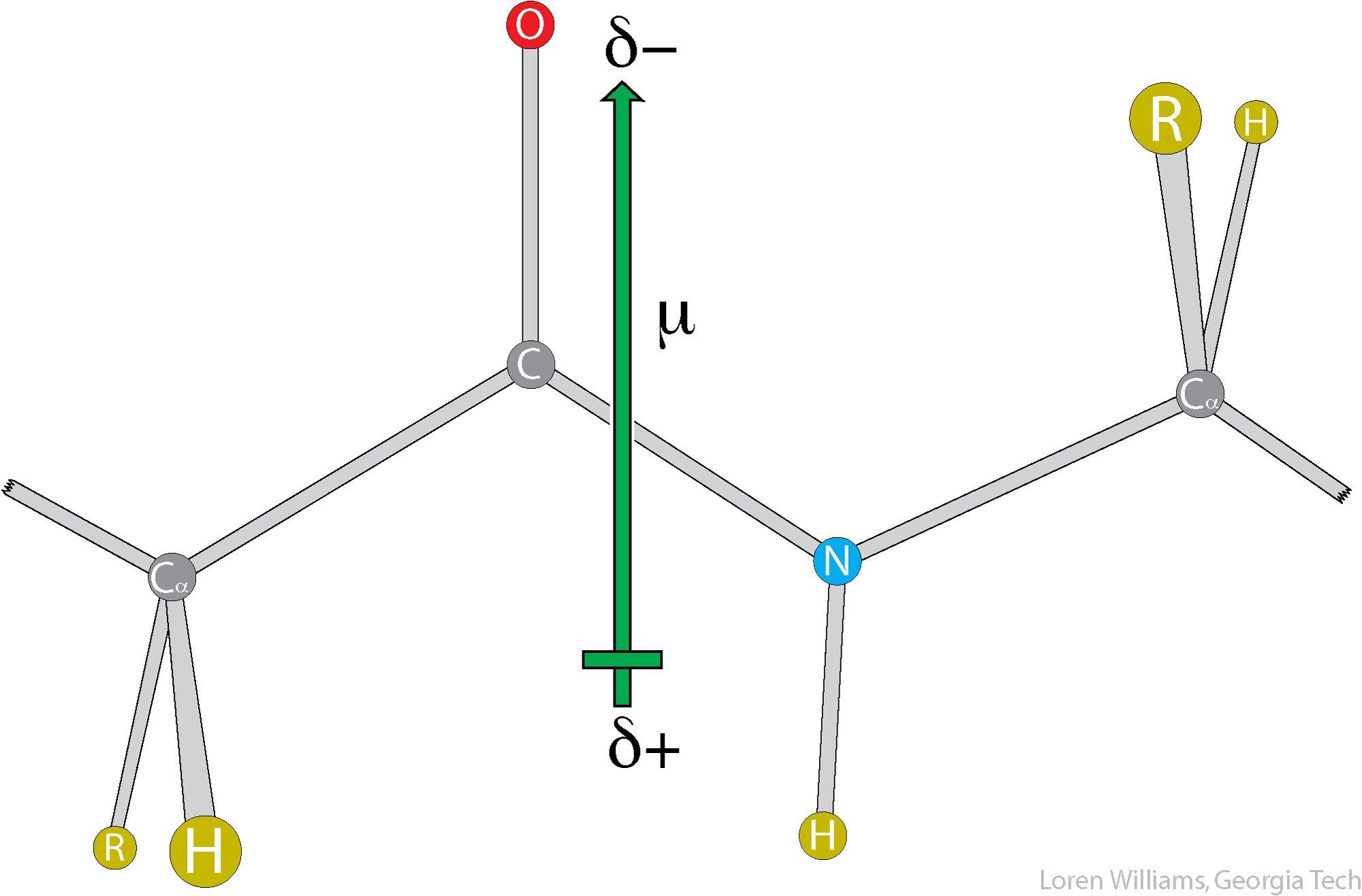

The orientation of the dipole moment of a peptide is approximately parallel to the N-H bond and is around 3.7 Debye in magnitude.

The large dipole moment of a peptide bond should lead one to expect that dipolar interactions are important in protein conformation and interactions. They are.

A dipole is surrounded by an electric field, which causes force-at-a-distance on nearby charged and partially charged species. Interactions between dipoles and ions are are called Charge-Dipole Interactions (or Ion-Dipole Interactions). Dipoles also interact with other dipoles (Dipole-Dipole Interactions), and induce charge redistribution (polarization) in surrounding molecules (Dipole-Induced Dipole Interactions). We will discuss each of these interactions separately in the sections below.

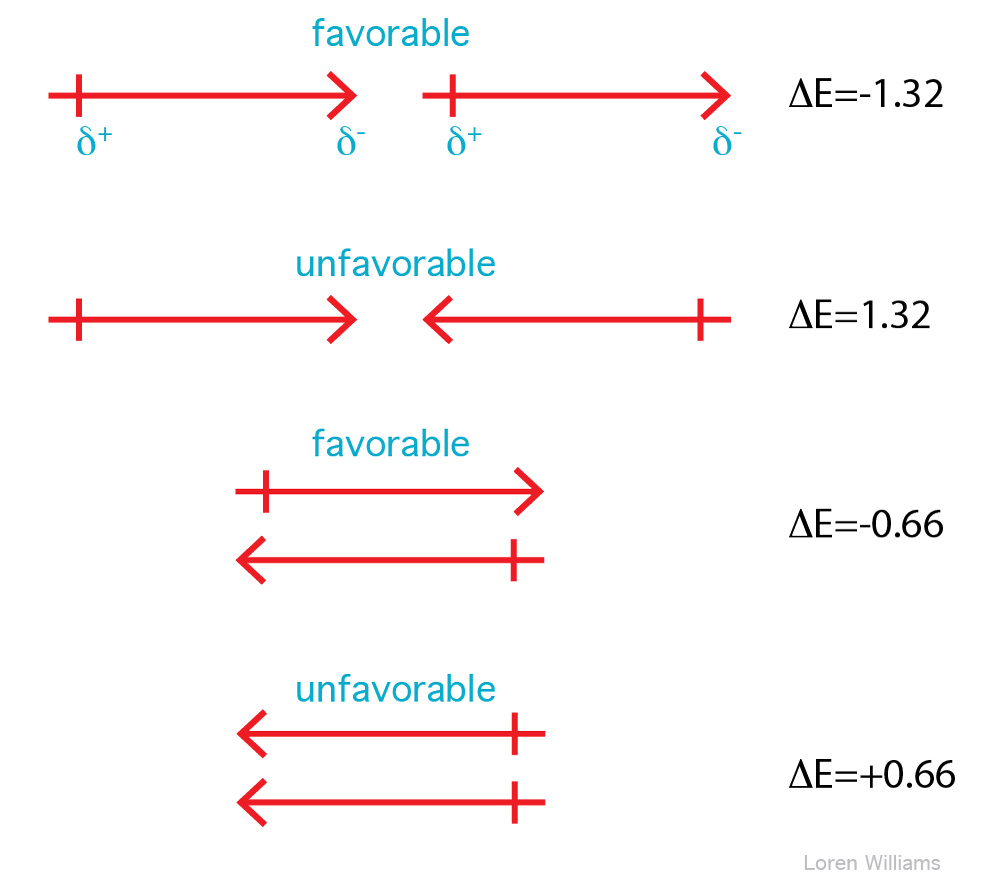

Two dipoles feel each other at a distance. The positive end of the first dipole is attracted to the negative end of the second dipole and is repelled by positive end. The strength of a dipole-dipole interaction depends on the size of both dipoles and on their proximity and orientations. The net interaction energy between two dipoles can be either positive or negative. Parallel end to end dipoles attract while antiparallel end to end dipoles repel. Listed below are the energies of interaction for various orientations of two dipoles with moments of 1 Debye at a distance of 5 Å in a medium of ε = 4.

In liquids the orientations of molecular dipoles change rapidly as molecules tumble about. However, dipole moments tend to orient favorably. Therefore, in liquid acetone for example, favorable dipole-dipole interactions outweigh unfavorable dipole-dipole interactions. Dipole-dipole interactions fall off with 1/r3.

A polarizable molecule tumbling in a solution of polar molecules is like a wind sock buffeted by shifting winds. The electron density of a polarizable molecule is shifted and deformed by the electric fields of the surrounding polar molecules.

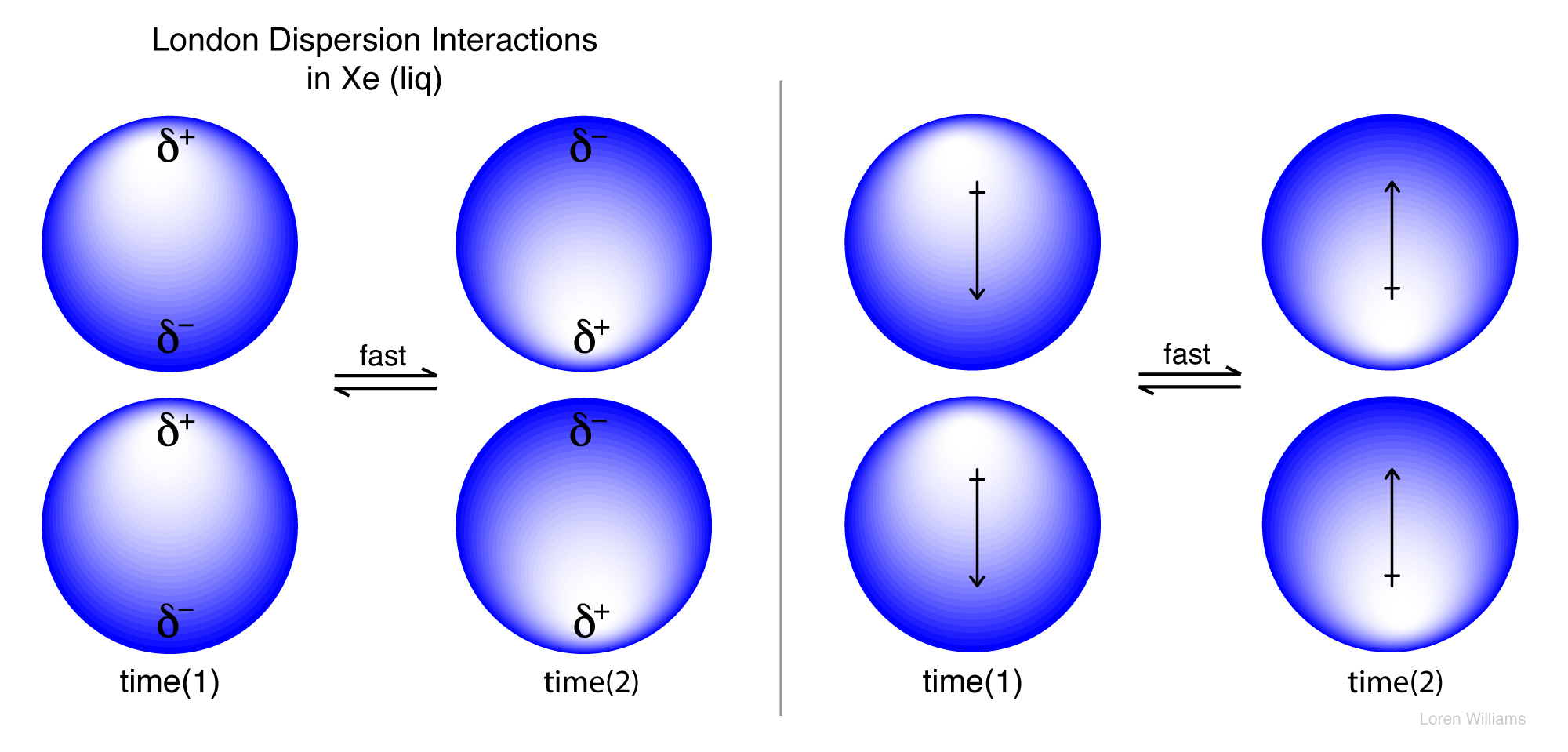

Any molecule with a dipole moment (or any ion) is surrounded by an electrostatic field. This electrostatic field shifts the electron density (alters the dipole moments) nearby molecules. A change in the dipole moment of one molecule by another (or by any external electric field) is called polarization. The ease with which electron density is shifted by an electronic field is called polarizability. Large atoms like xenon are more polarizable than small atoms like helium. Amino acid sidechains with π electrons, such as phenylalanine and tryptophan, are more polarizable than sidechains such as isoleucine, which lack π electrons.

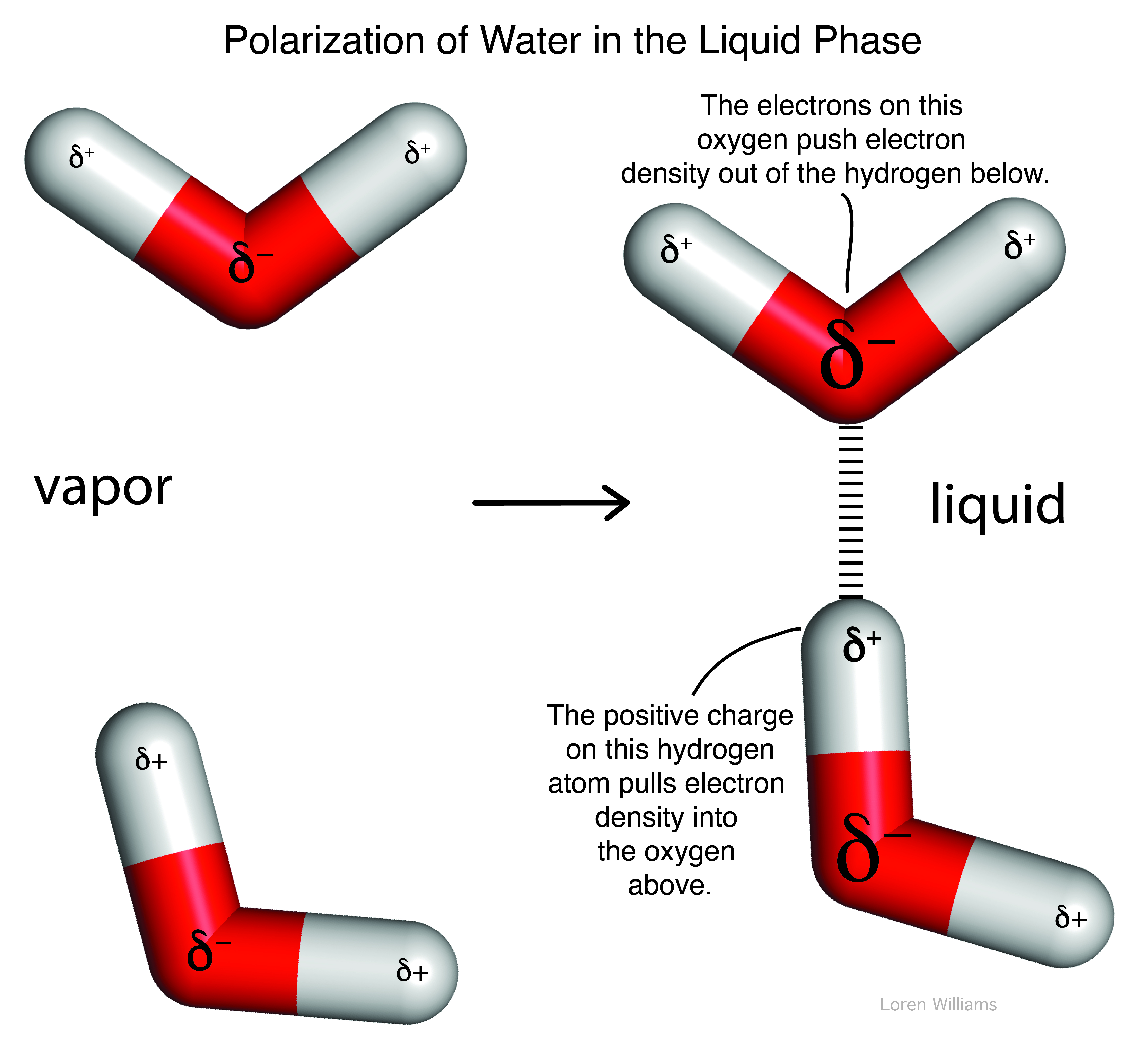

Dipole-induced dipole interactions are important even between molecules with permanent dipoles. A permanent dipole is perturbed by an adjacent dipole. For example, in liquid water (where molecules are close together), all water molecules are polarized. The permanent dipole of each water molecule polarizes all adjacent water molecules. The dipole of a water molecule induces change in the dipoles of all nearby water molecule.

Dipole-induced dipole interactions are always attractive and can contribute as much as 0.5 kcal/mole (2.1 kjoule/mole) to stabilization of molecular associations. Dipole-induced dipole interactions fall off with 1/r4. Formally charged species (Na+, Mg2+, -COO-, etc.) also polarize nearby molecules and induce favorable dipoles. The resulting interactions, called charge-induced dipole interactions (or ion-induced dipole interactions). These interactions are important, for example in protein structure, but are not broken out into a separate section in this document.

A molecule with a permanent dipole can interact favorably with cations and anions. This type of interaction is called a charge-dipole or ion-dipole interaction. Charge-dipole interactions are why sodium chloride, composed cationic sodium ions and anionic chloride ions, and other salts tend to interact well with water, and are very soluble in water, which has a strong dipole.

E. Fluctuating dipolar interactions (Dispersive interactions, London Forces).

We can see resonance all around us. A child on a swing, the tides in the Bay of Fundy and the strings on a violin all illustrate the natural resonant frequencies of physical systems. The Tacoma Narrows Bridge is one of the most famous examples of resonance.

Molecules resonate too. Electrons, even in a spherical atom like Helium or Xenon, fluctuate over time according to the natural resonant frequency of that atom. Even though chemists describe atoms like Helium and Xenon as spherical, if you could take a truly instantaneous snapshot of a spherical atom, you would always catch it in a transient non-spherical state. Xenon is spherical on average, but not at any instantaneous timepoint.

As electron density fluctuates, dipole moments also fluctuate. Therefore, all molecules and atoms contain oscillating dipoles. In all molecules that are close together (in any liquid or a solid, but not in a perfect gas) the oscillating dipoles sense each other and couple. They oscillate in synchrony, like the strings of a violin. The movements of electrons in adjacent molecules are correlated. Electrons in one molecule tend to flee those in the next, because of electrostatic repulsion. Coupled fluctuating dipoles experience favorable electrostatic interaction known as dispersive interactions.

Dispersive interactions are always attractive and occur between any pair of molecules (or non-bonded atoms), polar or non-polar, that are nearby to each other. Dispersive interactions increase with polarizability, which explains the trend of increasing boiling points (i.e., increasing strength of dispersive interaction) in the series He (bp 4.5 K), Ne (27K), Ar (87K), Kr (120 K) and Ze (165K). Dispersive interactions are the only attractive forces between atoms in these liquids. Without dispersive interactions there would be no liquid state for the Nobles. Dispersive interactions are especially strong for aromatic systems, which are very polarizable.

The total number of pairwise atom-atom dispersive interactions within a folded protein is enormous, so that dispersive interactions can make large contributions to stability. The strength of this interaction is related to polarizability. Tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine and histidine are the most polarizable amino acid sidechains, and form the strongest dipsersive interactions in proteins.

What about water? Even molecules with permanant dipoles, like water, experience dispersive interactions. About a 25% of the attractive forces between water molecules in the liquid are dispersive in nature.

Dispersive interactions fall off with 1/r6.

| Cation-Π interactions with benzene | |

|---|---|

| Ion | ΔH (kcal/mol) |

| Li+ | -38 |

| Na+ | -28 |

| K+ | -19 |

| NH4+ | -19 |

| (gas phase) | |

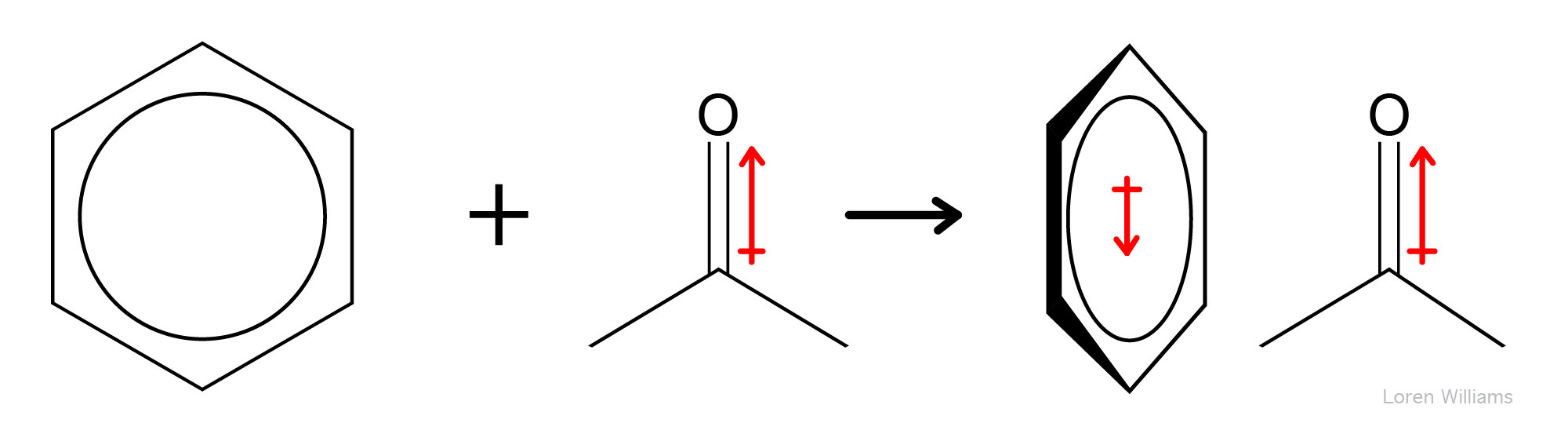

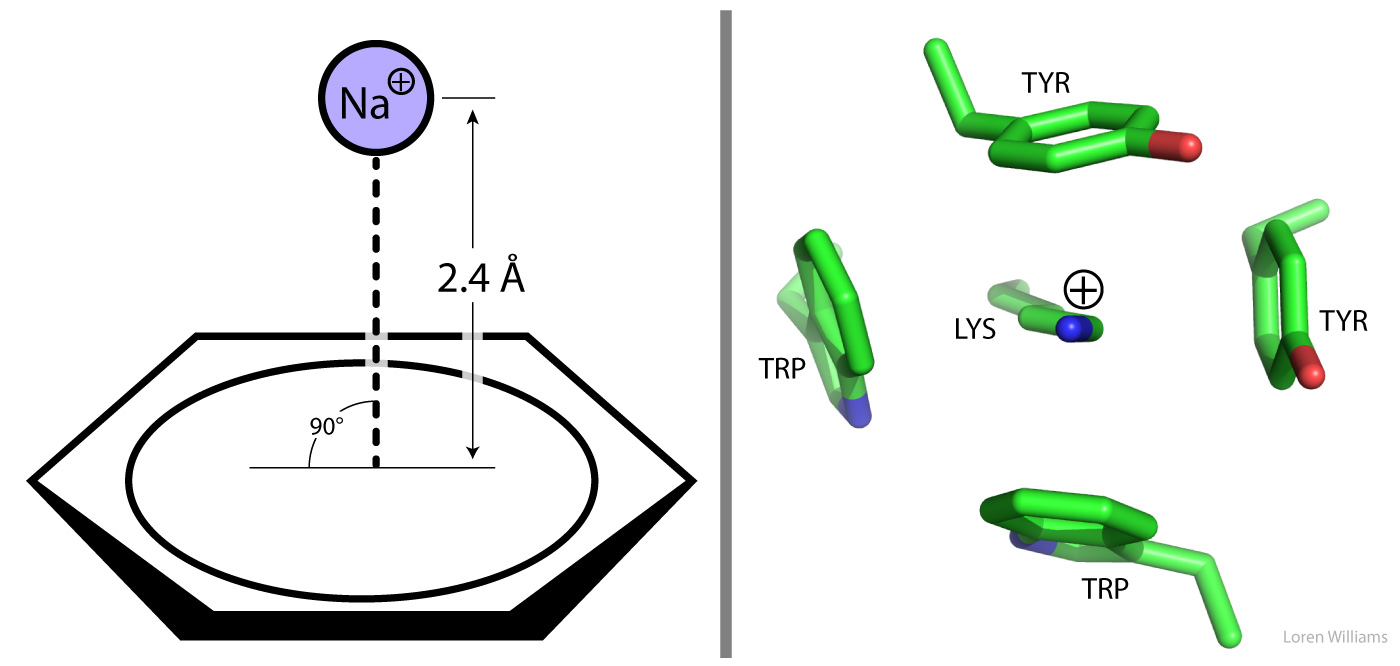

A Π-system, such as that of benzene, tryptophan, phenylalanine or tyrosine, focuses partial negative charge above and below the plane of the aromatic ring. A cation can interact favorably with this partial negative charge when the cation is near the face of the Π-system. In the most stable arrangment, the cation is centered directly over the Π-system and is in direct van der Waals contact with it. The table on the left shows gas phase interaction enthalpies, which are on the same order as the hydration enthalpies for these cations. Therefore, cation-Π interactions are roughly similar in strength to cation-dipole interactions formed between water and cations. Small ions with high charge density form stonger cation-Π complexes than larger ions. Electron withdrawing groups on the ring system weaken cation interactions while electron donating groups strengthen them.

Cation-Π interactions are important in protein structure. The guanidinium group of arginine and the ε-NH3+ of lysine engage in cation-Π interactions with aromatic protein sidechains. A favorable cation-Π pair contributes as much to protein stability as a good hydrogen bond or an electrostatic (charge-charge) interaction. Tryptophan is the most frequent π system in protein cation-Π pairs while arginine is the most frequent cation. Tryptophan and arginine can form extended coplaner assemblies.

The idea that a single hydrogen atom could interact simultaneously with two other atoms was proposed in 1920 by Latimer and Rodebush and their advisor, G. N. Lewis. Maurice Huggins, who was also a student in Lewis' lab, describes the hydrogen bond in his 1919 dissertation.

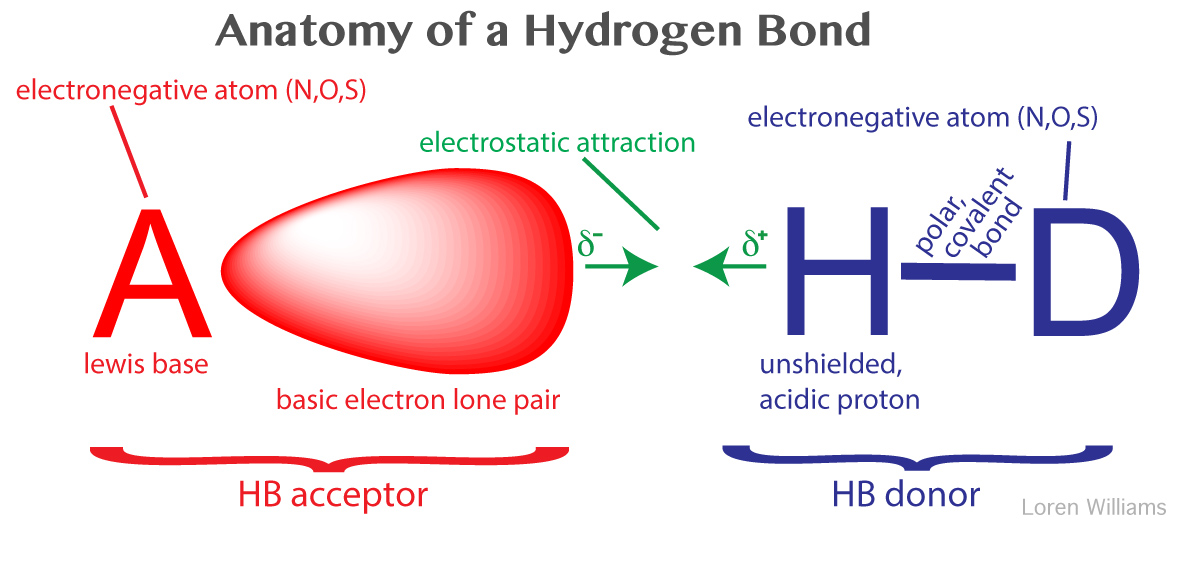

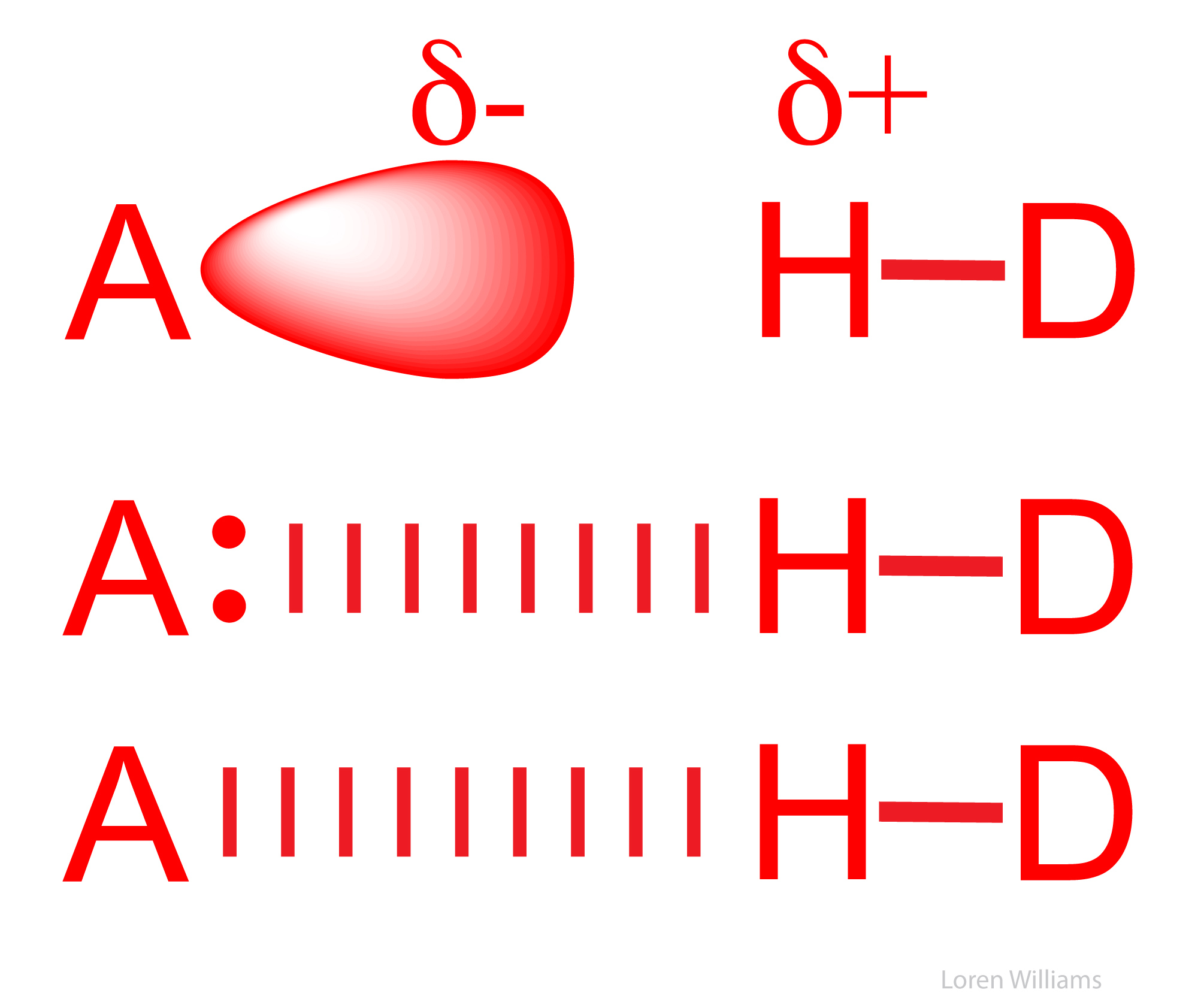

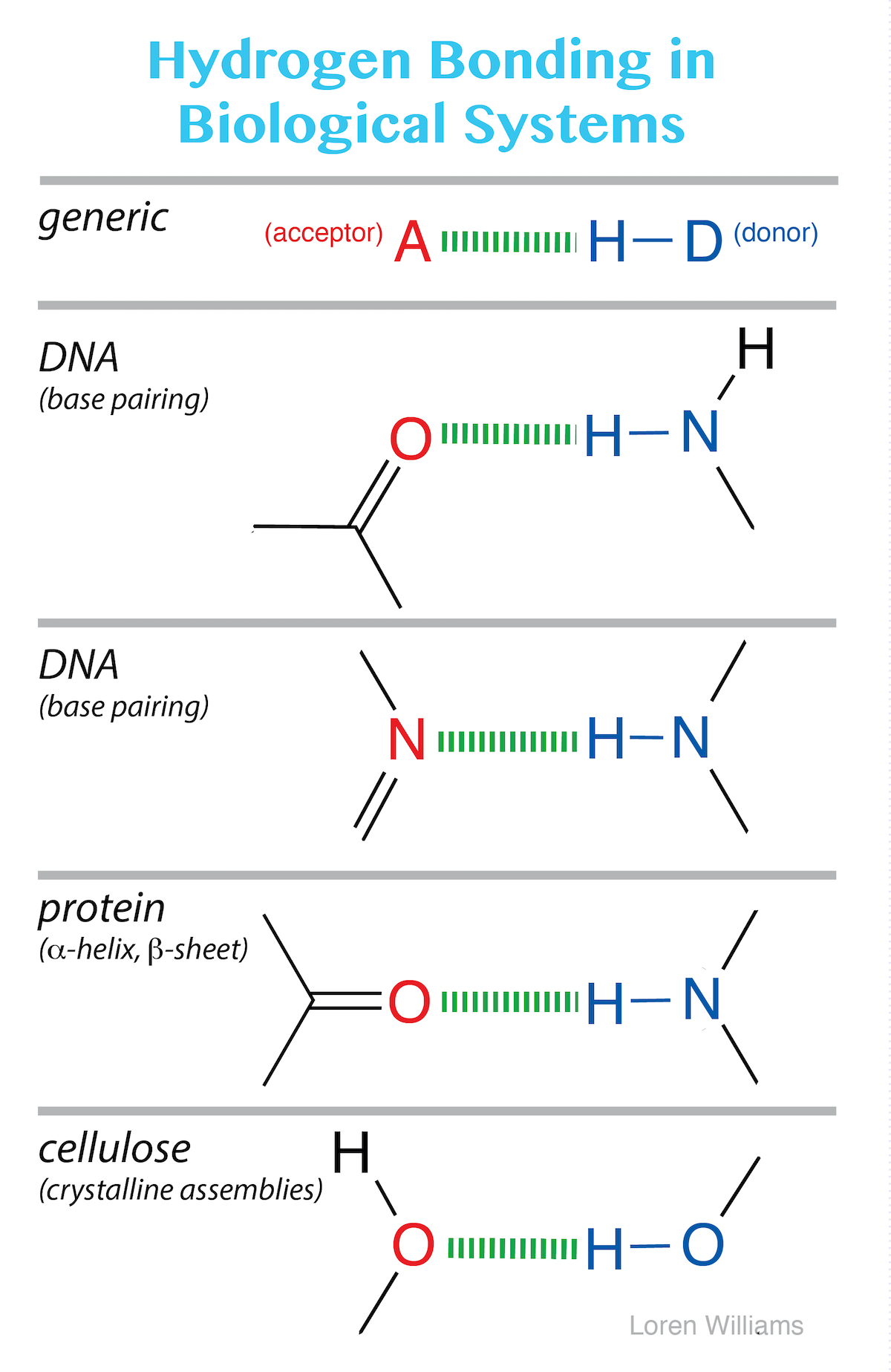

A hydrogen bond is a favorable interaction between an atom with a basic lone pair of electrons (a Lewis Base) and a hydrogen atom that has been partially stripped of its electrons because it is covalently bound to an electronegative atom (N, O, or S). In a hydrogen bond, the Lewis Base is the hydrogen bond acceptor (A) and the partially exposed proton is bound to the hydrogen bond donor (H-D).

Why hydrogen? Hydrogen is special because it is the only atom that (i) forms covalent sigma bonds with electronegative atoms like N, O and S, and (ii) uses the inner shell (1S) electron(s) in that covalent bond. When its electronegative bonding partner pulls the bonding electrons away from hydrogen, the hydrogen nucleus (a proton) is exposed on the back side (distal from the bonding partner). The unshielded face of the proton is exposed, attracting the partial negative charge of an electron lone pair. Hydrogen is the only atom that exposes its nucleus this way. Other atoms have inner shell non-bonding electrons that shield the nucleus.

A hydrogen bond is not an acid-base reaction, where the proton (H+) is fully transferred from H-D to A to form D- and HA+. However, the strength of a hydrogen bond correlates well with the acidity of donor H-D and the basicity of acceptor A. In a hydrogen bond, the H+ is partially transfered from H-D to A, but H+ remains covalently attached to D. The H-D bond remains intact.

The most common hydrogen bonds in biological systems involve oxygen and nitrogen atoms as A and D. Keto groups (=O), amines (R3N), imines (R=N-R) and hydroxyl groups (-OH) are the most common hydrogen bond acceptors in DNA, RNA, proteins and complex carbohydrates. Hydroxyl groups and amines/imines are the most common hydrogen bond donors. Hydroxyls and amines/imines can both donate and accept hydrogen bonds.

In traversing the Period Table, increasing the electronegativity of atom D strips electron density from the proton (in H-D), increasing its partial positive charge, and increasing the strength of any hydrogen bond. Thiols (-SH) can can both donate and accept hydrogen bonds but these are generally weak, because sulfur is not sufficiently electronegative. Hydrogen bonds involving carbon, where H-D equals H-C, are observed, although these are weak and infrequent. C is insufficiently electronegative to form good hydrogen bonds. Hydrogen bonds are essentially electrostatic in nature, although the energy can be decomposed into additional contributions from polarization, exchange repulsion, charge transfer, and mixing.

Hydrogen bond strengths form a continuum. Strong hydrogen bonds of 20-40 kcal/mole (82 to 164 kjoule/mole), generally formed between charged donors and acceptors, are nearly as strong as covalent bonds, Weak hydrogen bonds of 1-5 kcal/mole (4 - 21 kjoule/mole), sometimes formed with carbon as the proton donor, are no stronger than conventional dipole-dipole interactions. Moderate hydrogen bonds, which are the most common, are formed between neutral donors and acceptors are from 3 - 12 kcal/mole (12 - 50 kjoule/mole)).

A note on nomenclature. A hydrogen bond is not a bond. It is a molecular interaction (a non-bonding interaction). The unfortunate name given to this molecular interaction long ago has caused and will continue to cause all kinds of confusion. Do not confuse hydrogen bonds with real bonds. They are not the same thing at all.

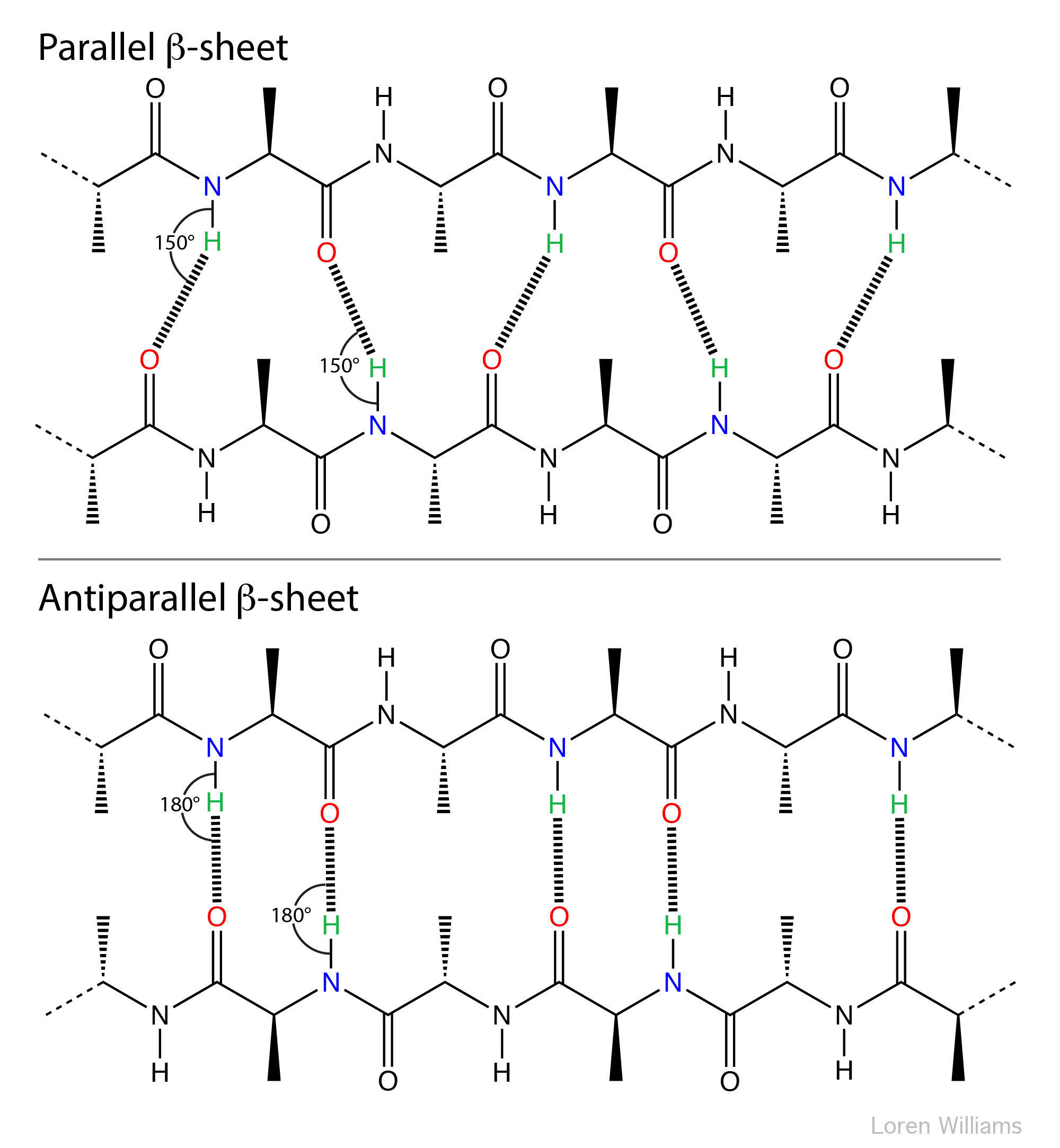

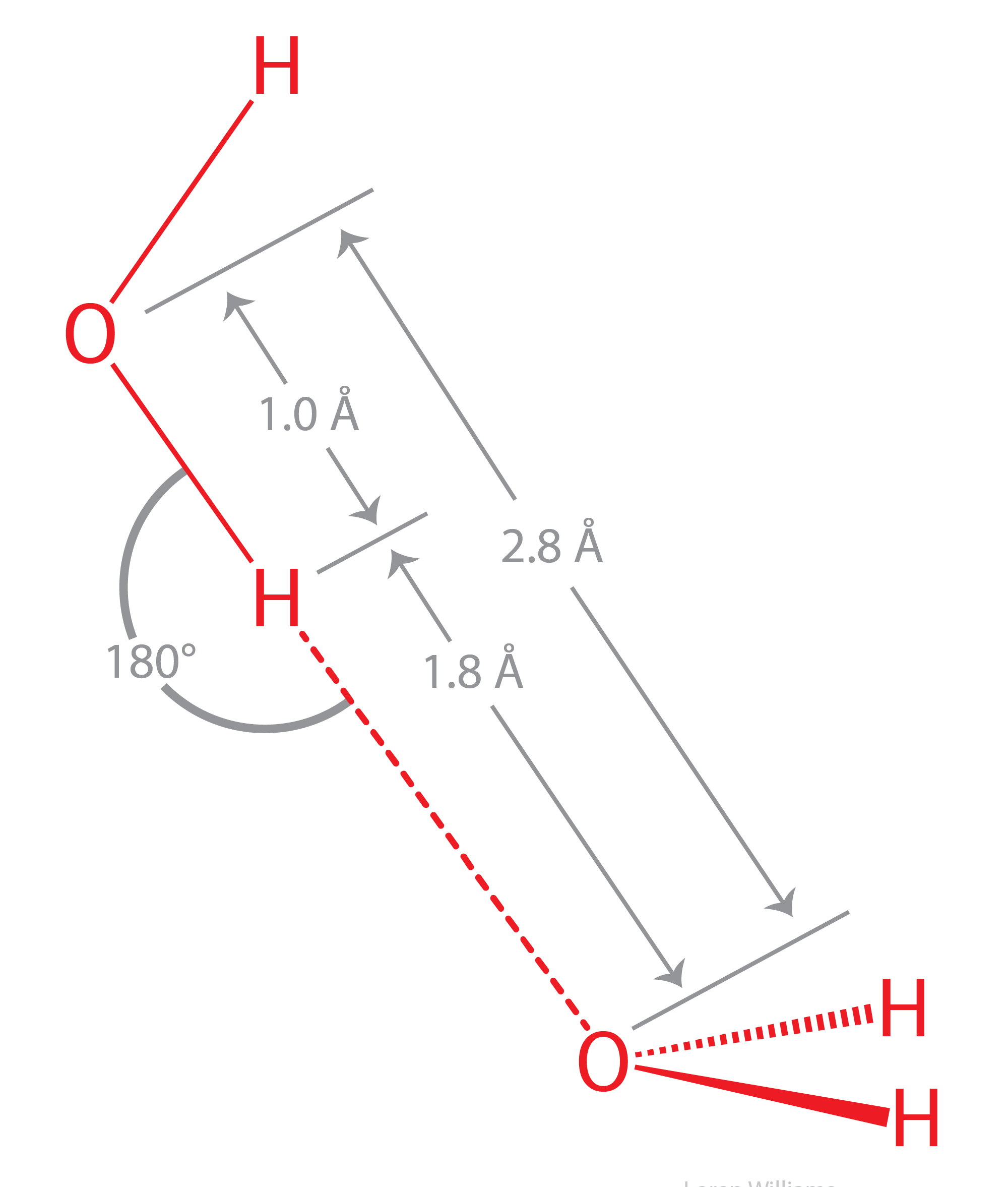

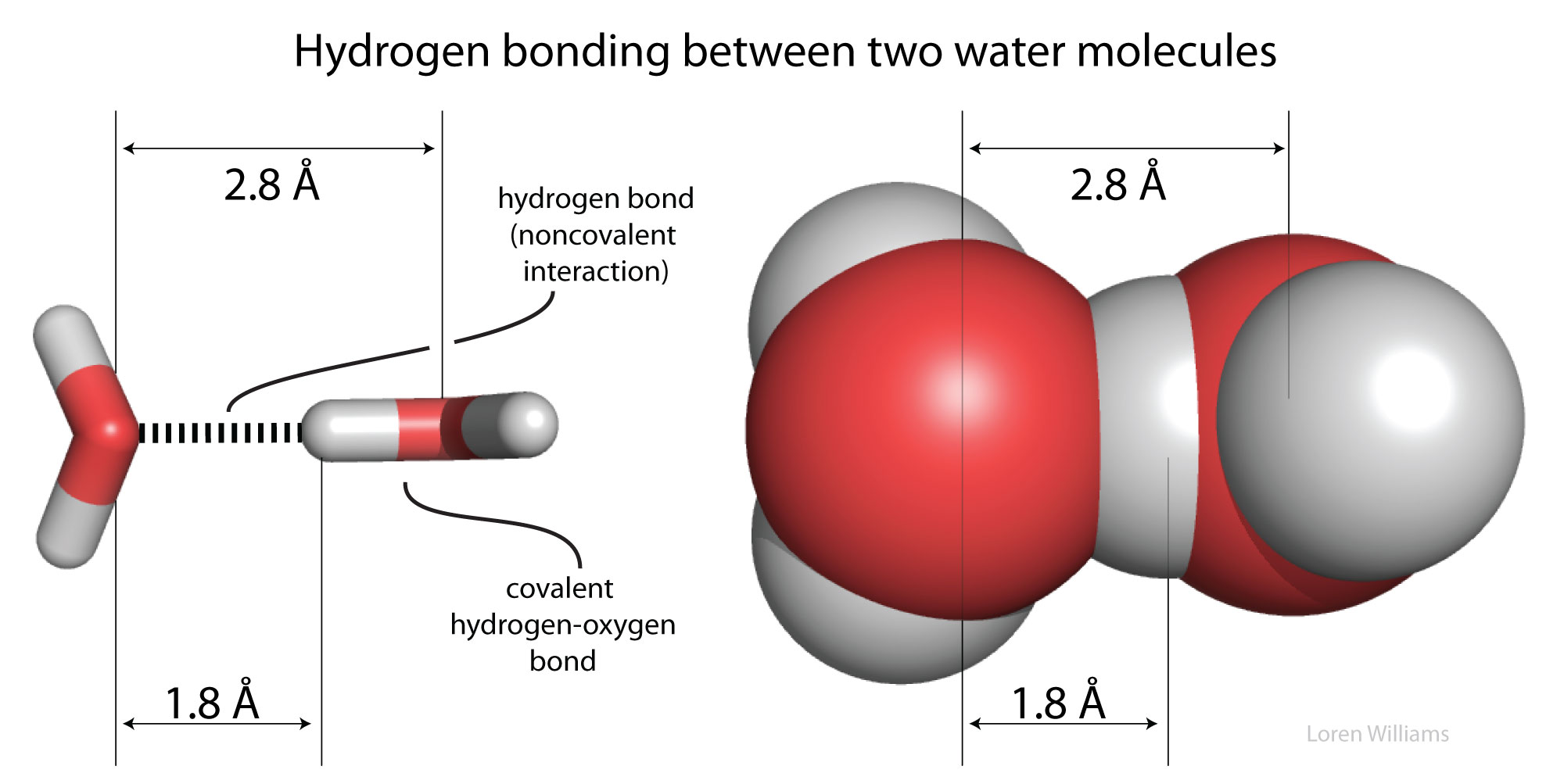

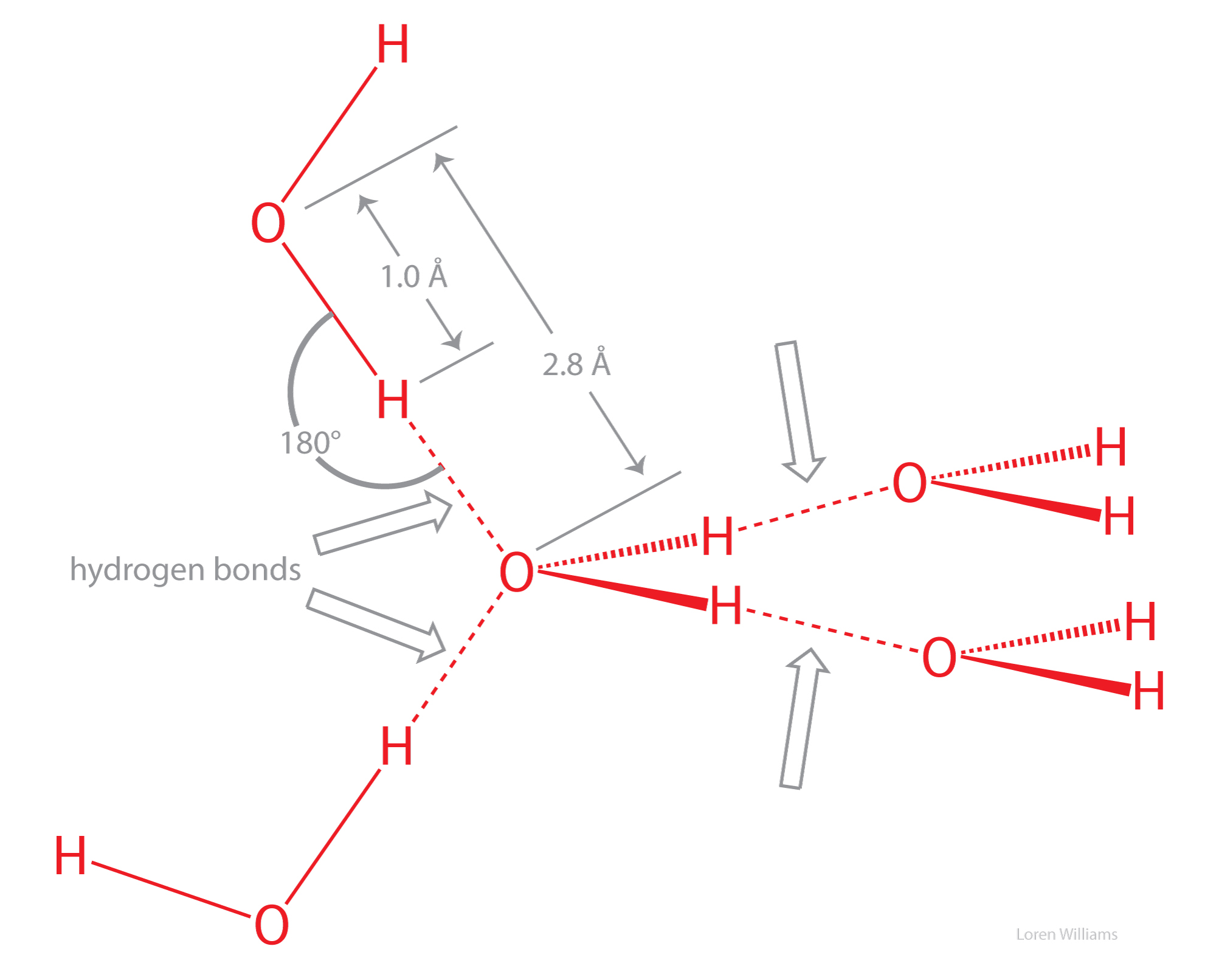

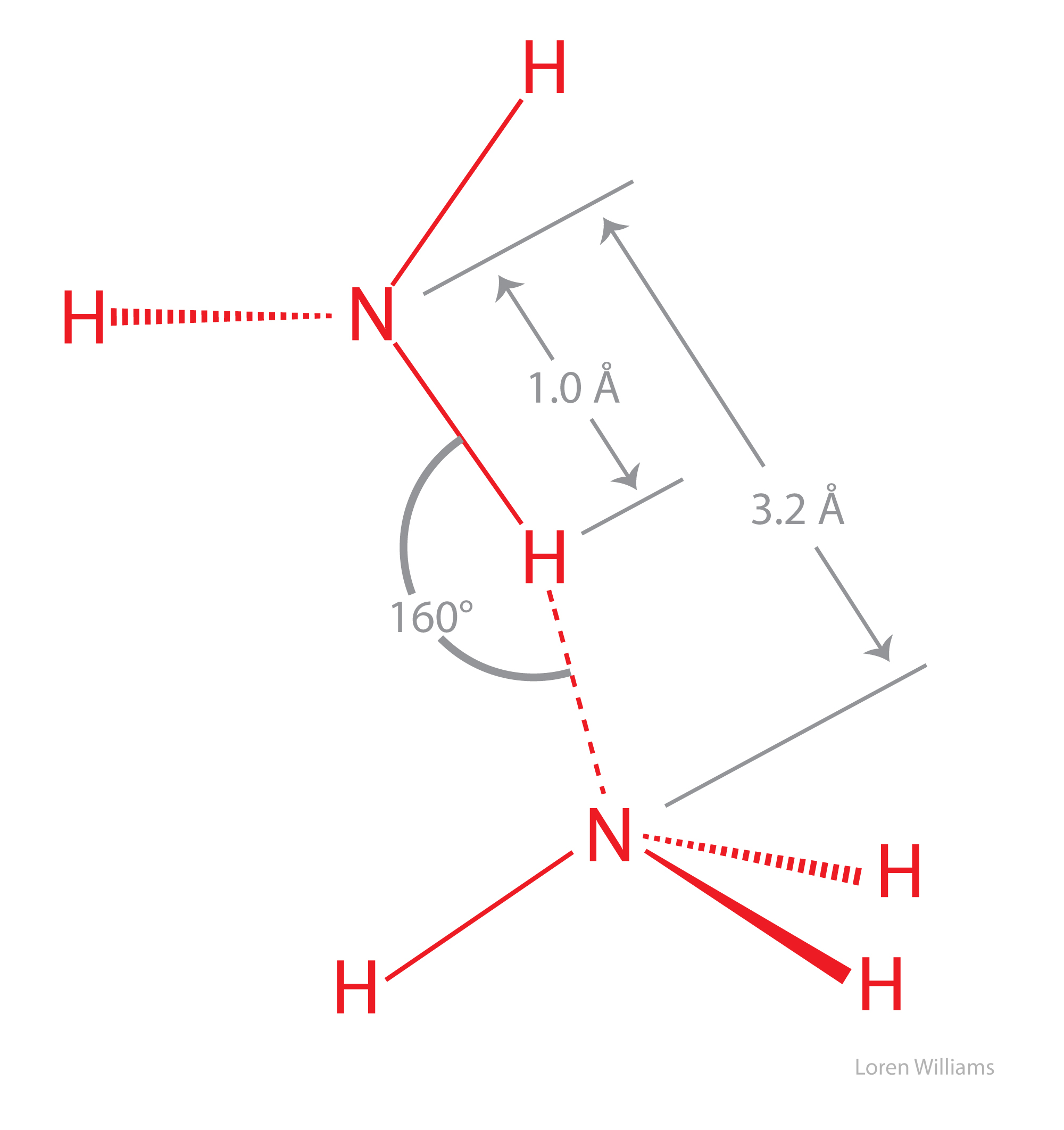

The geometry of a hydrogen bond can be described by three quantities, the D to H distance, the H to A distance, and the D to H to A angle. The distances depend on the atom types of A and D. If both A and D are oxygen atoms, then optimally, H to A = 1.8 Å and D to H = 1.0 Å. The most stable hydrogen bonds are close to linear (D to H to A angle of 180°). The hydrogen bonds in antiparallel β-sheets are linear, while the hydrogen bonds in parallel β-sheets are non-linear.

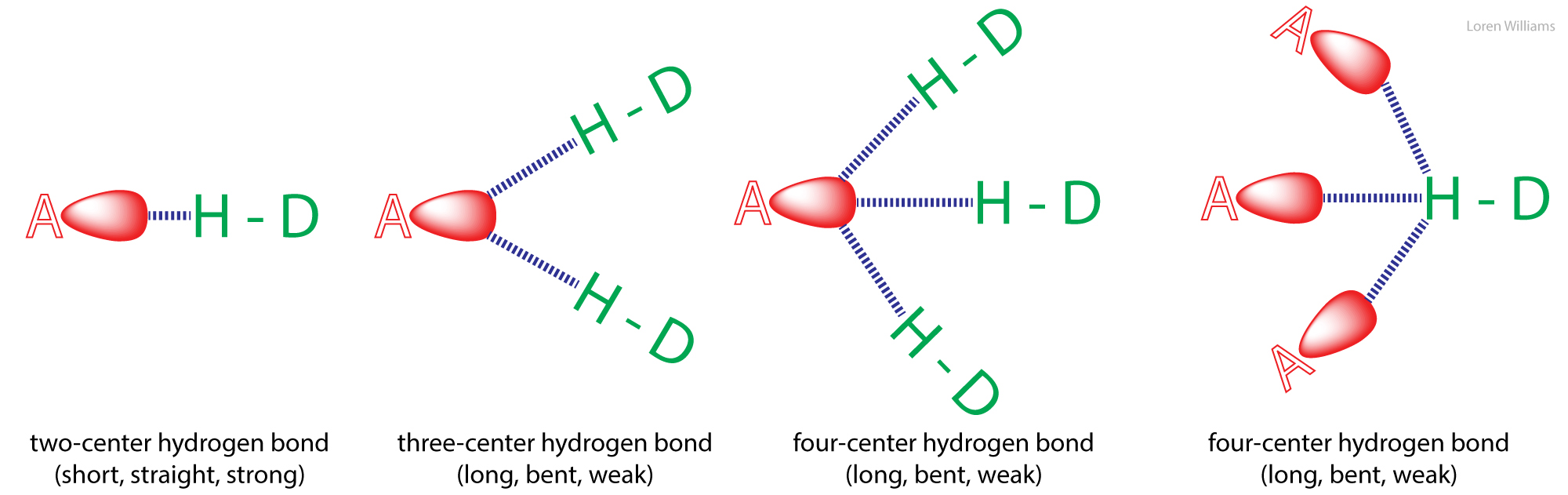

Hydrogen bonds can be two-center (as in a β-sheets and ideal ice), three-center, or four-center. Two-center hydrogen bonds are generally shorter, more linear, and stronger than three- or four-center hydrogen bonds. Three-center bonds are sometimes called bifurcated while four centered hydrogen bonds are sometimes called trifurcated.

Hydrogen atoms are not observable by x-ray crystallography as applied to proteins and nucleic acids. So a geometric description of hydrogen bonding that is dependent on the hydrogen position is not always practical. In these cases one is usually limited to analysis of the D to A distance. It is common to ascribe a hydrogen bond if a distance between A and D is less than the sum of their van der Waal radii. However this limit is probably too conservative. The best criteria for an H-bond is a distance of less than 3.4 Å between D and A.

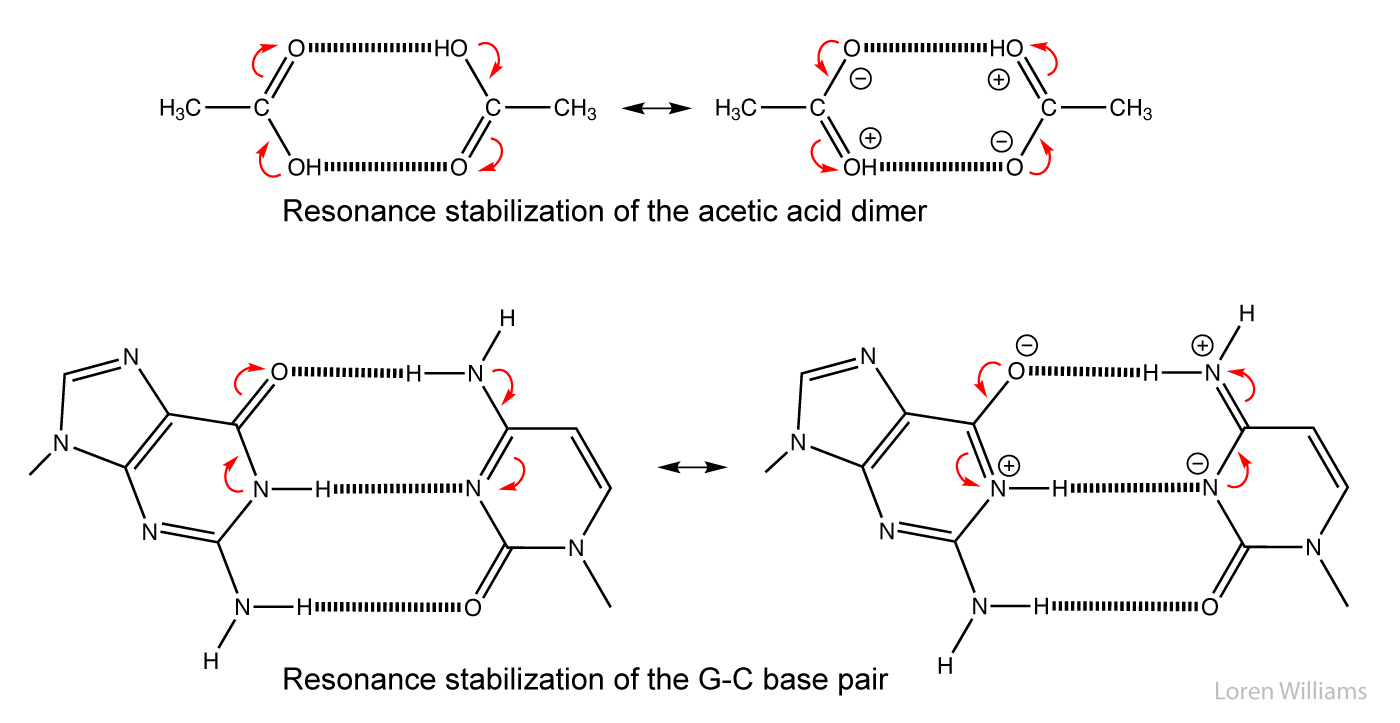

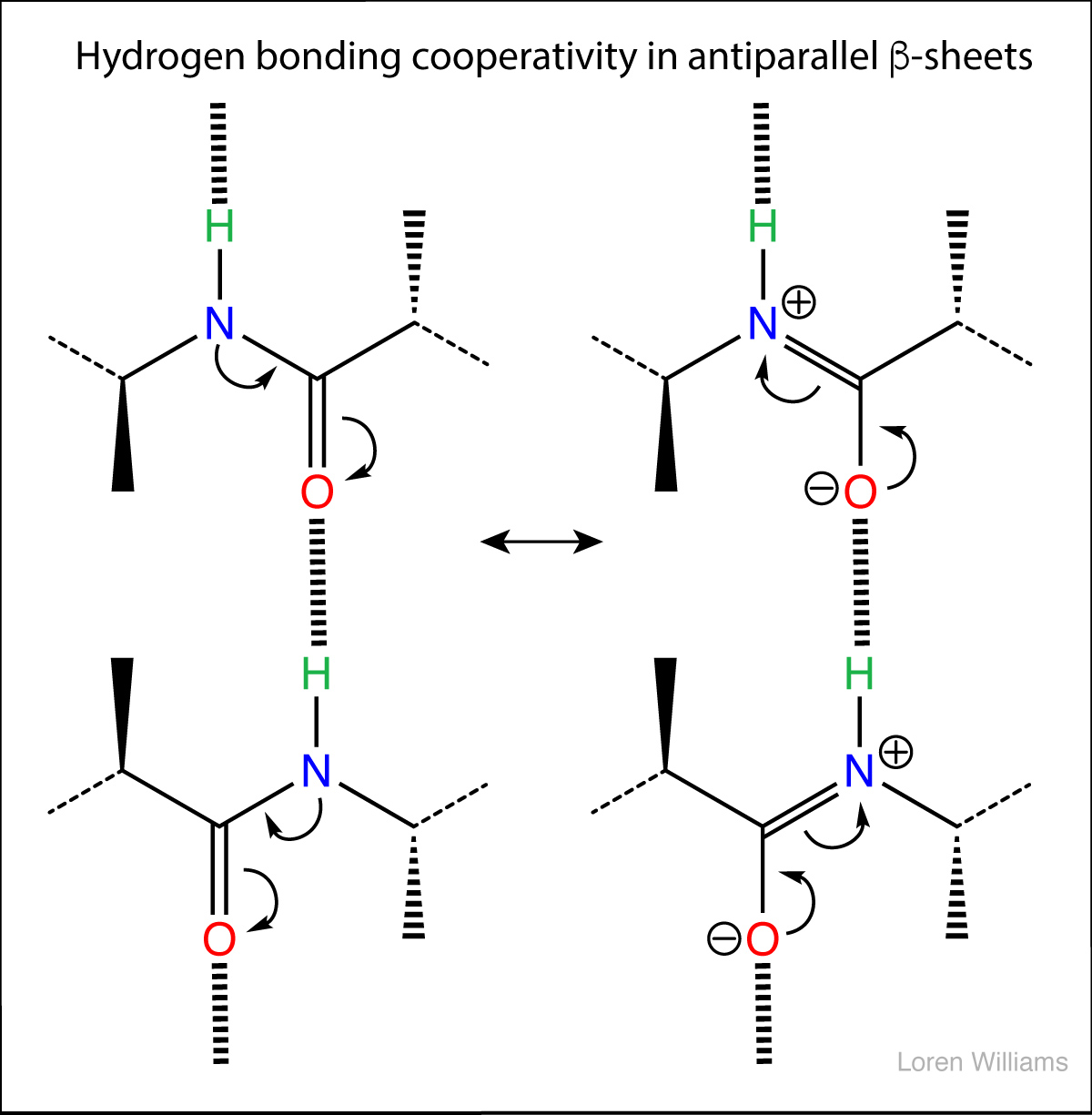

In biological systems, hydrogen bonds are frequently cooperative and are stabilized by resonance involving multiple hydrogen bonds. In systems with multiple hydrogen bonds, the strength of one hydrogen bond is increased by a adjacent hydrogen bond. For example in the hydrogen-bonded systems below (the acetic acid dimer), the top hydrogen bond increases both the acidity of the hydrogen, and the basicity of the oxygen in the bottom hydrogen bond. Each hydrogen bond makes the other stronger than it would be in isolation. Cooperativity of hydrogen bonding is observed in base pairing and in folded proteins.

H. Water - the liquid of life.

A drop of water, if it could write out its own history, would explain the universe to us - Lucy Larcom.

Water is the most perfect traveler because when it travels it becomes the path itself -Mehmet Murat ildan.

Water is the vehicle of nature - Leonardo da Vinci.

Water, the most abundant compound on the surface of the Earth and probably in the universe, is the medium of biology. Most cells are around 65% water by volume and 70% by mass. Living organisms have developed sophisticated mechanisms for appropriating and preserving water.

Water is a powerful solvent for ions and polar substances and is a poor solvent for non-polar substances. Water causes certain amphipathic molecules (with both polar and non-polar functionalities) to spontaneously form compartments. In water, membranes assemble and proteins fold.

Water has a unique ability to shield charged species from each other. Electrostatic interactions between ions are highly attenuated in water. The electrostatic force between two ions in solution is inversely proportional to the dielectric constant of the solvent. The dielectric constant of water (80.0) is huge. It is over twice that of methanol (33.1) and over five times that of ammonia (15.5). Water is a good solvent for salts because the attractive forces between cations and anions are significantly reduced by water.

Water is also the most frequent chemical actor in biochemistry. Between a third and a half of known biochemical reactions involve consumption or production of water. In a cell, a given water molecule frequently and repeatedly serves as a reaction substrate, intermediate, cofactor, and product. Water is the most abundant and universal metabolite in biological chemistry, accounting for over 99% of metabolites in an E. coli by molar concentration. Essentially all biological molecules, large and small, are products of or substrates for biochemical reactions that chemically transform water. Water is never absent from or physically separated from biological macromolecules, organic cofactors, and metals, but readily combines with, withdraws from, and intercedes in their transformations. In biological systems, water is fully integrated into processes of bond making and bond breaking. For biological water, there is no meaningful distinction between medium and chemical participant.

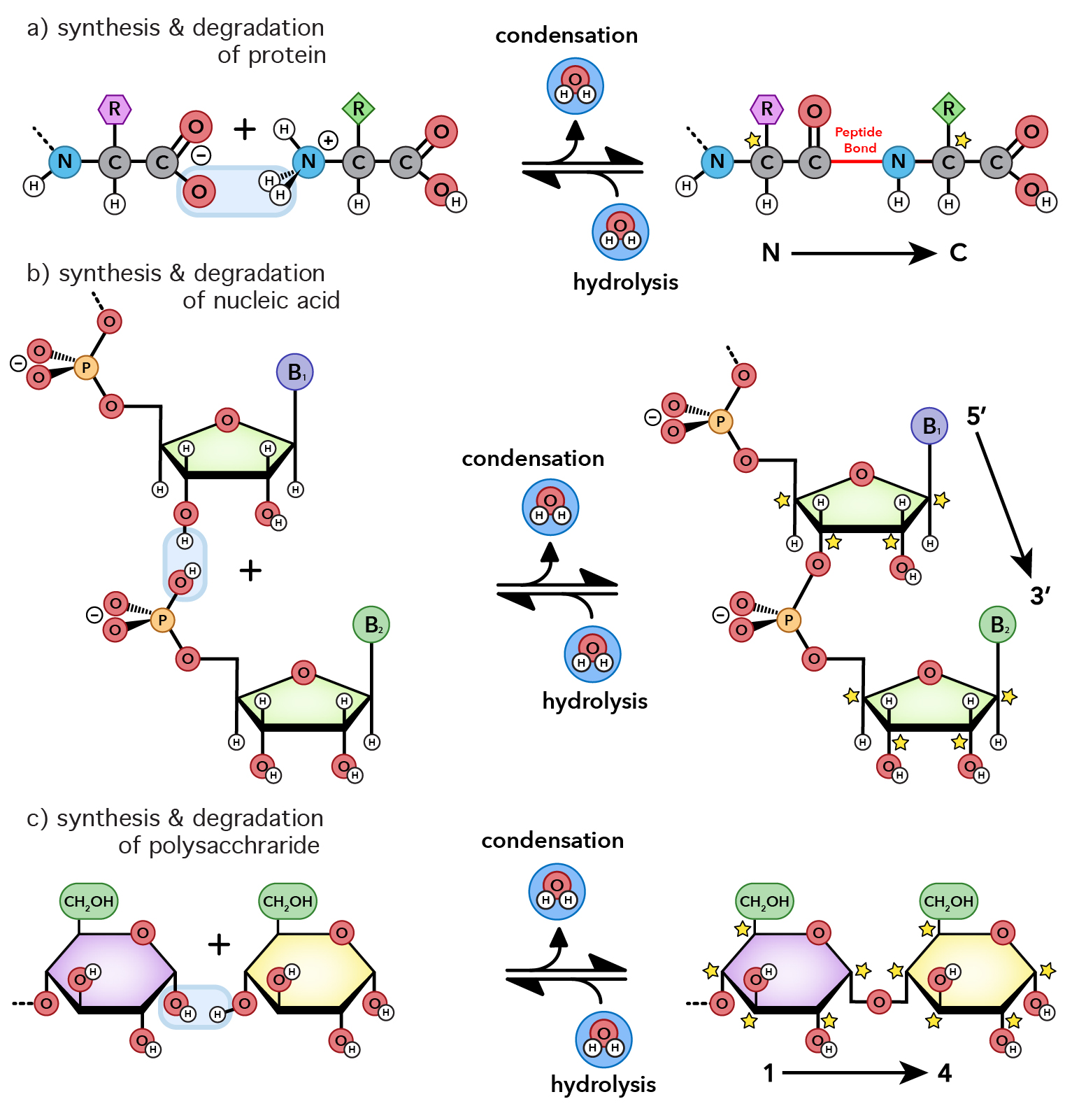

The use of water as a metabolite is seen in biopolymer synthesis. All biopolymers are formed by condensation dehydration reactions, which link small building blocks and chemically produce water (shown here). Specifically, a peptide bond in a protein is formed by condensation of amino acids. In the net reaction, two amino acids join together and produce one water molecule to form a peptide bond. Water is a product in the chemical reaction of peptide bond formation. In the reverse reactions, biopolymers are degraded by hydrolysis reactions, which chemically consume water. Water is a reactant in the chemical reaction of peptide bond breaking.

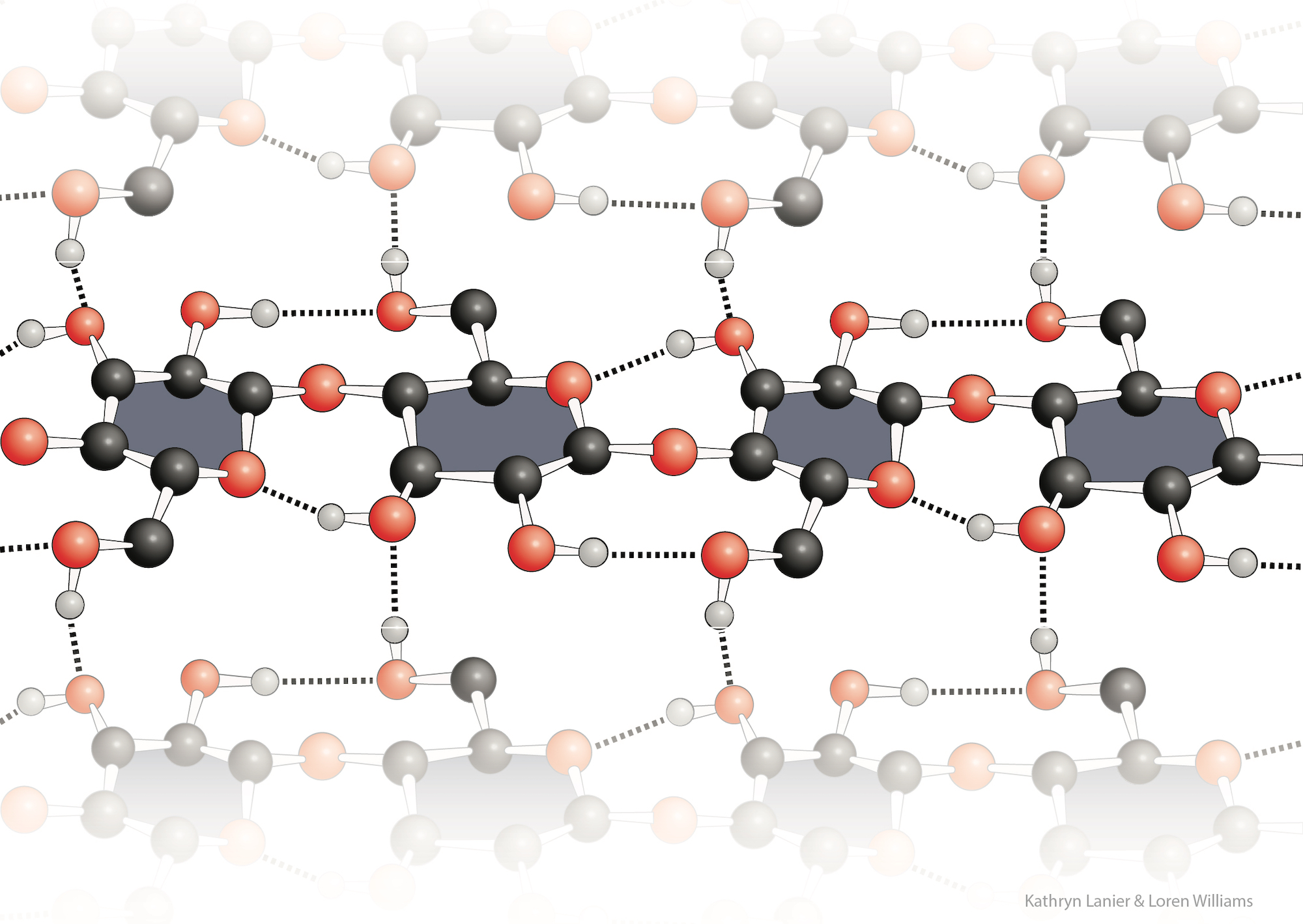

Polynucleotides (DNA and RNA) are formed by condensation of nucleotides (dG, dT, dA, dC for DNA), which are in turn formed by condensation of smaller substructures. Triglycerides and phospholipids are formed by condensation of glycerol with fatty acids and other molecules. Cellulose, the most abundant polymer in the biosphere, is formed by condensation of glucose.

In sum: Water is the medium of biology (the solvent) and is fully integrated into the most basic and universal chemical reactions of biology. Stay hydrated.

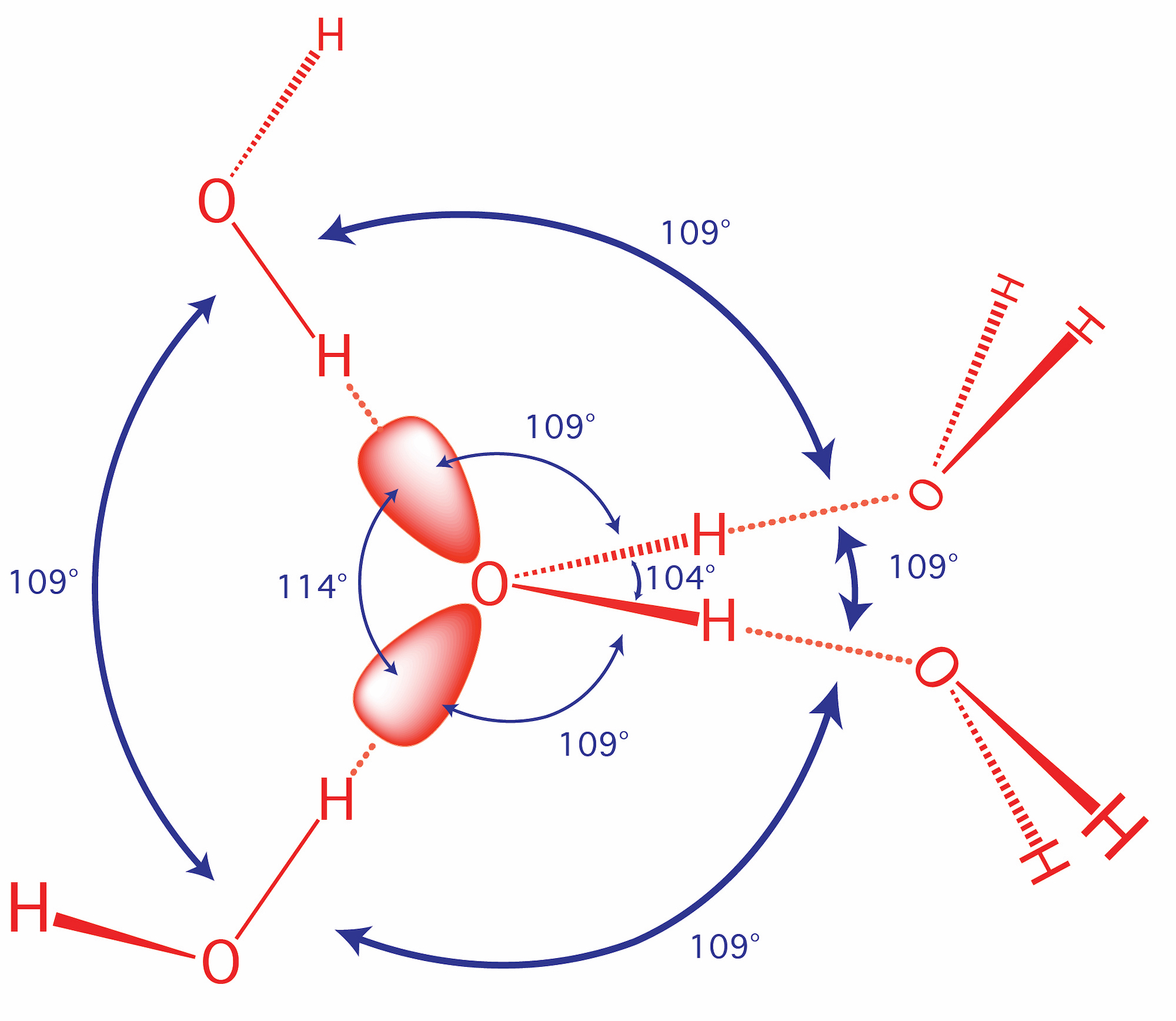

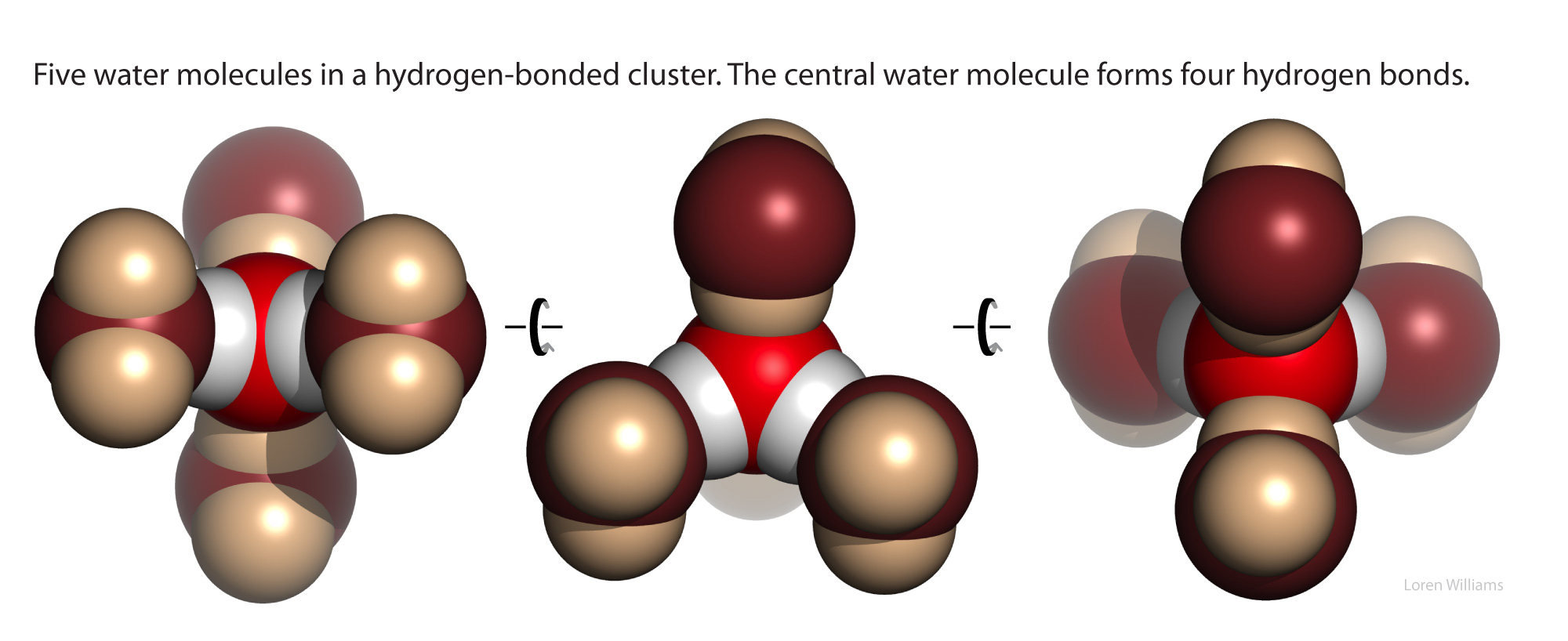

Water is intrinsically self-complementary. In liquid or solid water, all the atoms of every water molecule, utilizing the entire surface of the molecule, engage in ideal hydrogen bonding interactions with surrounding water molecules. All the HB donor and acceptor sites of any water molecule find perfect geometric matches in the HB donors and acceptors of surrounding water molecules. Liquid and solid water have the highest density of ideal hydrogen bonds (per volume) of any material. In condensed phases (liquid or solid) of water, the hydrogen bonding groups of each water molecule are complementary to the hydrogen bonding groups of the watery surroundings.

Water has a balanced number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors (two of each). In condensed phases, every water molecule acts as a donor in two hydrogen bonds and an acceptor in two hydrogen bonds, each with ideal geometry. The self-complementarity of water is emergent on the condensed phase. Isolated or small clusters of water molecules do participate in self-complementary interactions.

Strong self-complementary forces between water molecules cause very high melting temperature, boiling temperature, heat of vaporization, heat of fusion and surface tension. Water puffs up (increases volume) when it freezes; Ice floats. The heat of vaporization of water (540 cal/g) is over twice that of methanol (263 cal/g) and nearly ten times that of chloroform (59 cal/g).

A water molecule (H2O) can form strong hydrogen bonds, with either hydrogen bond donors or acceptors.

Hydrogen bonds cause violations of van der Walls surfaces. The hydrogen-bonding distance from H to O is around 1.8 Å, which is less than the sum of the O and H van der Waals radii (rO=1.5 Å; rH=1.0 Å). Also notice that the hydrogen-bonding distance from O to O is around 2.8 Å, which is less than twice the van der Waals radius of oxygen (rO=1.5 Å).

Oxygen is highly electronegative, and gains partial negative charge by withdrawing electron density from the two hydrogen atoms to which it is covalently bonded, leaving them with partial positive charges. Water is an excellent hydrogen bonding solvent. The coordinates of a water molecule linked by hydrogen bonds to two other water molecules are here [coordinates].

The coordinates of a very small ice cube are here [coordinates]. For additional information on water, see the section on water and the hydrophobic effect.

The oxygen of a water molecule has four filled valence orbitals (sp3 hybridized) that form a modestly distorted tetrahedron. Two of the electron pairs form covalent bonds with hydrogen atoms and two are non-bonding. The non-bonding lone pairs take more space than the bonding lone pairs, causing the distortion from a perfect tetrahedron. It is useful to imagine that a water molecule is a tetrahedron with negative charge on two apexes and positive charge on two apexes.

Oxygen, which is highly electronegative, withdraws electron density from the hydrogen atoms to the extent that they are essentially bare protons on their exposed sides (distal to the oxygen). The charge distribution of a water molecule (partial negative charge on oxygen and partial positive charge on hydrogen) is shown below.

X-ray and neutron diffraction of crystalline ice shows that each water molecule is engaged in four hydrogen bonds with intermolecular oxygen-oxygen distances of 2.76 Å. Each oxygen atom is located at the center of a tetrahedron formed by four other oxygen atoms. Each hydrogen atom lies on a line between two oxygen atoms and forms a covalent bond to one oxygen (bond length: 1.00 Å) and a hydrogen bond to the other (hydrogen bond length: 1.76 Å). The tetrahedral shape of an individual water molecule is projected out into the surrounding crystal lattice. The hydrogen atoms are not located midway between oxygen atoms. For additional information see the section on hydrogen bonding interactions

Water molecules in the crystalline state are not closely packed, resulting in tiny cavities of empty space within the crystal. The cavities are formed because the directionality of water-water interactions dominates water-water packing considerations. Small cavities in the solid lattice but not in the liquid are the reason that water increases in volume upon freezing (i.e., ice floats). There are many degrees of freedom in hydrogen bond donor/acceptor relationships that are interconverted by cooperative rotations. Water molecules readily rotate in ice.

You can learn a lot about water (H2O) by thinking about ammonia (NH3). A comparison of ammonia to water shows the significance of the self-complementarity of water, where the geometries of HB donors and acceptors of any given water molecule complement those of surrounding water molecules An ammonia molecule is non-complementary, with three donor sites (N-H's) and one acceptor site.

A isolated ammonia molecule, just like a water molecule, can form strong hydrogen bonds with either hydrogen bond donors or acceptors. Ammonia is more basic than water, and therefore ammonia is a better hydrogen bond acceptor than water.

In the crystalline and liquid states, the lone pair of electrons on each nitrogen is shared by multiple hydrogen bond donors. The hydrogen bonds are bifurcated and trifucated, as described above (see figure 20). The hydrogen bonds in crystalline and liquid are are long, bent and weak.

The boiling point of ammonia is −33 °C, much lower than that of water (100 °C), indicating that molecular interactions in NH3(liq) are significantly weaker than in H2O(liq). The coordinates of an ammonia molecule are here [coordinates].

In the liquid state, water is not as ordered as in the crystalline state. In the liquid state at O degrees C a time-averaged water molecule is involved in around 3.5 intermolecular hydrogen bonds. Some of them are three- and four-centered. Liquid water is more dense than solid water. Never-the-less, the macroscopic properties of liquid water are dominated by the directional and complementary cohesive interactions between water molecules.

It is a general property of the universe that mixing is usually spontaneous. Water and ethanol, or N2(g) or O2(g), or red marbles and blue marbles will spontaneously mix. Entropy increases upon mixing because the number accessible states increases upon mixing. There are more ways things can be mixed than unmixed.

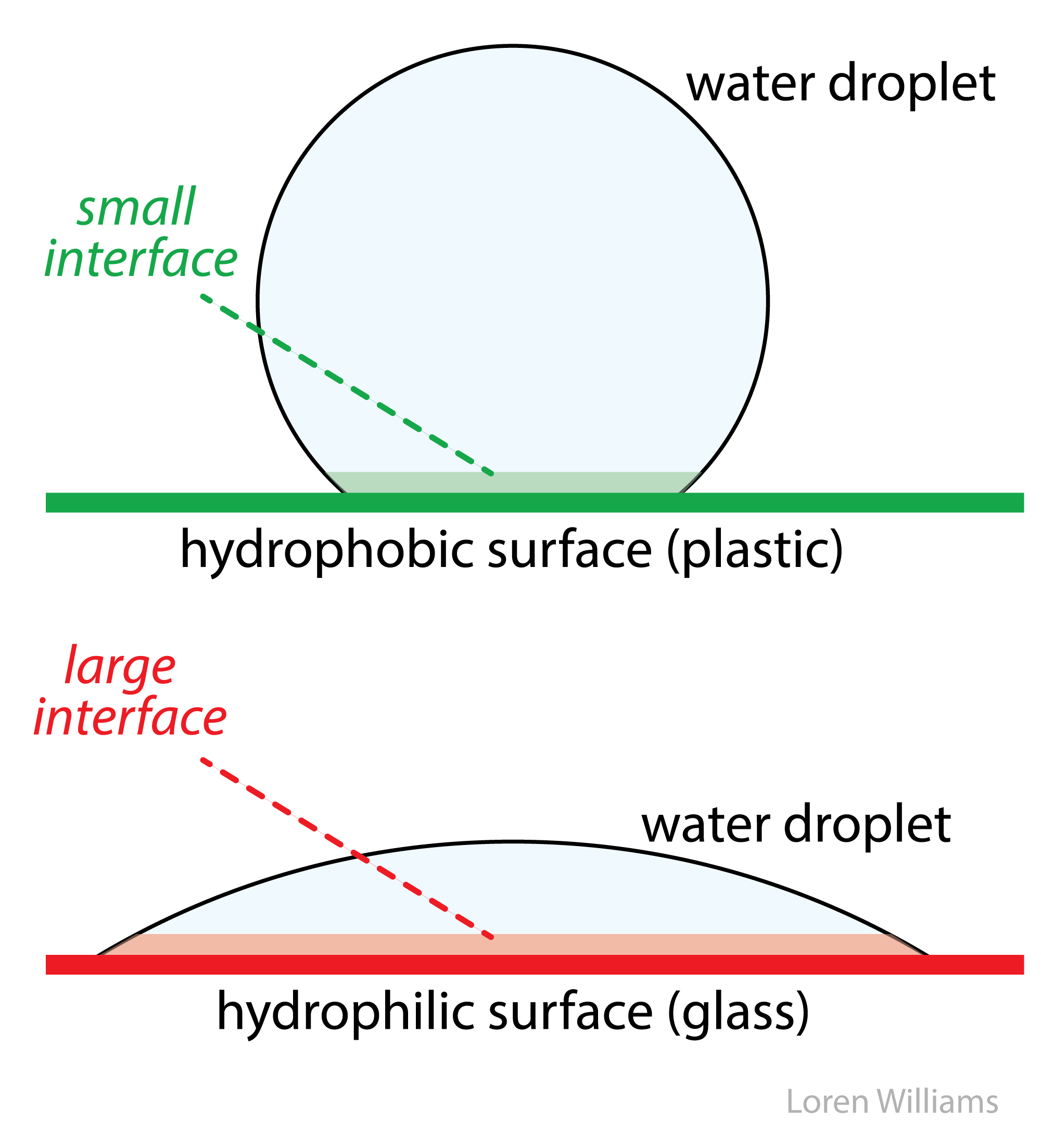

But, if you mix olive oil and water by vigorous shaking, the two substances will spontaneously unmix. Spontaneous unmixing is strange and unusual. The unmixing of olive oil and water is the hydrophobic effect in action. The hydrophobic effect is the insolubility of oil and other non-polar substances in water.

The spontaneous unmixing of olive oil and water emanates from water, not from attractive interactions between the olive oil molecules. Water actively drives olive oil out of water. Olive oil is a passive participant. Olive oil self-interacts primarily by dispersive interactions. Water interacts with olive oil by dispersive plus dipole induced-dipole interactions. The strength of molecular interactions of olive oil with water molecules are a bit stronger than those in pure olive oil.

The hydrophobic effect can be understood only by understanding water. The hydrophobic effect is an indirect consequence of strong directional interactions between water molecules and the complementarity of those interactions. The hydrophobic effect is fully a property of water; it a consequence of the distinctive molecular structure of water and the unique cohesive properties of water. (Many textbooks contain superficial or incorrect explanations. 'Like likes like' does not explain the basis of the hydrophobic effect.)

A note on nomenclature. A hydrophobic molecule is non-polar, cannot form hydrogen bonds, is insoluble in water and is soluble in non-polar solvents (such as CCl4 or cyclohexane or olive oil). Hydrocarbons (CH3CH2CH2 .... CH2CH3) are hydrophobic. A hydrophilic molecule, like glucose, is polar, can form hydrogen bonds and is soluble in water. Cellulose (a polymer of glucose), is polar and forms hydrogen bonds, and is hydrophilic, but is insoluble in water because of strong intermolecular cohesion. An amphipath is a schizophrenic molecule that in one region is hydrophobic and in another region is hydrophobic. Amphipaths can form assemblies such as membranes and micelles. Phospholipids are amphipaths. A hydrotrope is an amphipath that is too small to assemble. ATP is a hydrotrope.

We can understand the hydrophobic effect in two separate steps - first a molecular step, then a thermodynamic step.

Water-water hydrogen bonds rule. Water-water hydrogen bonds are intact even when oil and water are forcibly mixed or when water sits on plastic surface. Water keeps hydrogen bonds intact when it is forced into contact with a non-hydrogen bonding substance at the cost of strange geometry and lack of rotational and translational freedom. This "interfacial water" is very weird, and is unstable because it has low entropy. Water gains entropy and stability by minimizing the amount of interfacial water. Water droplets adjust their shape to minimize contact with a hydrophobic surface and water forces hydrophobic molecules out of aqueous solution.

In bulk water, intermolecular forces are essentially isotropic (extending in all directions). In bulk, a water molecule can rotate and still maintain hydrogen bonding interactions. At a hydrophobic interface the interactions are anisotropic (directional) because the hydrophobic substance does not form hydrogen bonds. The motions of water are restrained at the interface. So the mixing of oil and water has a negative ΔS. This entropic effect leads to an unfavorable free energy of mixing oil and water (ΔG=ΔH-TΔS > 0).

Our description of the hydrophobic effect as an entropic phenomenon is correct only at low (biological) temperatures. We stay in this realm because biochemists don't have to worry about high temperatures. And the term 'hydrophobic bond' is a misnomer and should be avoided, even though Walter Kauzmann, the discoverer of the hydrophobic effect, did often use that phrase.

The molecular descriptions of the hydrophobic effect above can be understood by the thermodynamic parameters enthalpy (ΔH, indicates changes in molecular interactions) and entropy (ΔS, indicates changes in available rotational, translational, vibrational states, etc). A hydrocarbon engages in favorable molecular interactions with water in aqueous solution. We know this because the transfer of a mole of hydrocarbon from pure hydrocarbon to dilute aqueous solution has an enthalpy of around zero. So why don't oil and water mix? It is the water. Water drives non-polar substances out of the aqueous phase.

As illustrated below, in the aqueous phase a region of relatively low entropy (high order) water forms at the interface between the aqueous solvent and a hydrophobic solute.

When hydrocarbon molecules aggregate in aqueous solution, the total volume of interfacial water decreases. Thus the driving force for aggregation of hydrophobic substances arises from an increase in entropy of the water. The driving force for aggregation does not arise from intrinsic attraction between hydrophobic solute molecules.

If one considers the entropy of the hydrocarbon molecules alone, a dispersed solution has greater entropy, and is more stable, than an aggregated state. Similarly, a protein may appear to have greater entropy in a random coil than in a native state. Only when the entropy of the aqueous phase is factored into the equation can one understand the separation of water and oil into two phases, and the folding of a protein into a native state.

For many purposes it is useful to approximate of DNA as a rod coated with anionic charge. In aqueous solution the negative rod is surrounded by counterions (cations such as Na+, K+ and Mg2+ and/or by polyamines). Counterion release explains much of the salt dependencies of DNA melting, DNA-protein interactions, RNA folding and DNA condensation.

The high density of negative charge on the rod causes strong radial electric fields. The electric field is strong near the rod and weak far from the rod. These electric fields lead to steep radial gradients of the counterion concentration. The counterion concentration is high near the rod and low far from the rod. The "condensed" counterions are mobile, but are constrained to a small volume near to the DNA.

Theoretical considerations show that the local concentration of a monovalent cation such as K+ near the surface of DNA is around 2 molar. The reasons are not obvious, but the concentration of K+ surrounding DNA is largely independent of the K+ concentration in bulk solution. The electrostatic environment surrounding DNA does not depend on the bulk concentration of counterions.

DNA Melting. When DNA melts, the strands separate. Strand separation releases condensed counterions.

This relationship explains why the stability of double stranded DNA increases (with higher Tm) as salt concentration (ionic strength) increases. Application of Le Chatelier's principle shows that addition of counterions pushes the equilibrium to the left, toward the duplex.

Protein-DNA Interactions. Counterions are released when a cationic protein binds to DNA.

High salt destabilizes DNA-protein complexes. Cation release explains this salt dependence. Application of Le Chatelier's principle shows that addition of counterions pushes the equilibrium to the left, toward dissociated DNA and dissociated protein.

If the bulk salt concentration is low, there is a large entropic gain from counterion release, and the protein binds tightly to the DNA. If the bulk salt concentration is high, the entropic gain from counterion release is small, and the protein binds weakly.

DNA condensation. Genomic DNAs are very long molecules. The 160,000 base pairs of T4 phage DNA extend to 54 microns. The 4.2 million base pairs of the E. coli chromosome extend to 1.4 millimeters. In biological systems, long DNA molecules must be compacted to fit into very small spaces inside a cell, nucleus or virus particle. The energetic barriers to tight packaging of DNA arise from decreased configurational entropy, bending the stiff double helix, and intermolecular (or inter-segment) electrostatic repulsion of the negatively charged DNA phosphate groups. Yet extended DNA chains condense spontaneously by collapse into very compact, very orderly particles. In the condensed state, DNA helixes are separated by one or two layers of water. Condensed DNA particles are commonly compact toroids. DNA condensation in aqueous solution requires highly charged cations such as spermine (+4) or spermidine (+3). Divalent cations will condense DNA in water-alcohol mixtures. The role of the cations is to decrease electrostatic repulsion of adjacent negatively charged DNA segments. The source of the attraction between nearby DNA segments is not so easy to understand. One possible source of attraction are fluctuations of ion atmospheres in analogy with fluctuating dipoles between molecules (London Forces).

K. Introduction

Polymers are large molecules formed by covalently linking many small monomers into long chains. Polyethylene, used to make plastic bottles and bags, is a synthetic polymer with molecular formula (-C2H4-)n. The number of linked monomers (n) is very large in polyethylene and the molecular weight is around 5 million Daltons.

Living systems have many kinds of specialized polymers but universally express and utilize three types; polynucleotide (DNA and RNA), polypeptide (protein) and polysaccharide (cellulose, glycogen, etc.).

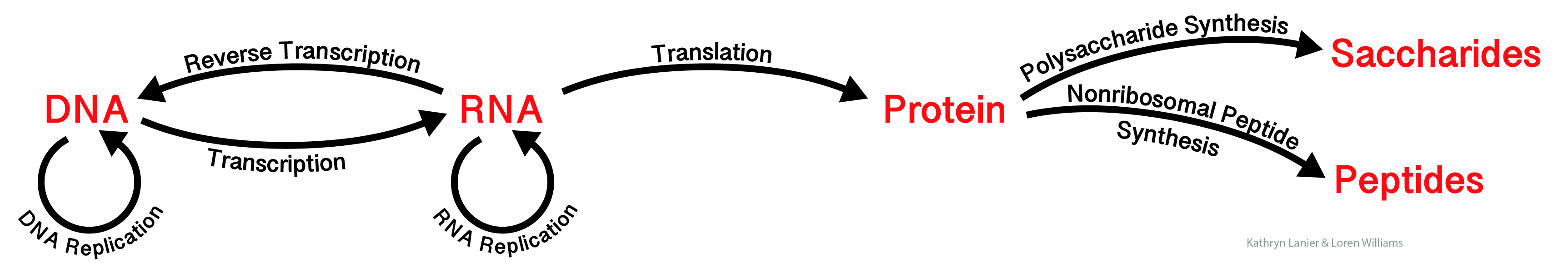

The "Central Dogma of Molecular Biology" describes how information flows between biopolymers. Biological information is defined by sequences of linked monomer units. Information flow is constrained to well-defined pathways among a small number of biopolymer types, which are universal to all living systems.

Here we have extended the Central Dogma to include non-ribosomal peptides and carbohydrates.

Monosaccharides, like nucleotides and amino acids, can be linked to encode information. Monosaccharides are the letters of the third alphabet of life (after the nucleotide alphabet and the amino acid alphabet). Oligomers of various sugars store and transmit information. For example carbohydrates provide cell-cell communication through cell surface interactions.

Nonribosomal peptides (NR peptides) are produced in bacteria and fungi and encode information in specific sequences. NR peptides are composed of a diverse alphabet of monomers. This alphabet is far larger than the 20 amino acid alphabet used by the translational system. NR peptides are synthesized by large multiprotein assemblies, are shorter than translated proteins, but are informationally dense.

The molecular interactions within and between biopolymers are astonishing compared to those of monomers. We say it like this: extraordinary molecular interactions observed in biological systems are emergent upon polymerization. Emergent properties are those of a sum (the polymer) that the parts (the monomers) do not have. It is not possible to predict the properties of biopolymers from the properties of their monomers. In the sections below we will explain and illustrate the emergent properties of biopolymers.

An aside; Why this section? Biochemistry textbooks can provide a lot of important detail about various types of polymers. However, DNA, RNA, polypeptide, and polysaccharide are described in isolation of each other, in separate chapters. This author (who has taught biochemistry for a long time) believes that biopolymers have important shared attributes (e.g., all universal biopolymers are self-complementary) and understanding the universal features of biopolymers should precede getting into the weeds of each type of biopolymer.

In the sections below we explain how universal biopolymers:

L. Making and breaking biopolymers.

How are universal biopolymers made? Each biopolymer is built by covalently linking members of well-defined and modestly-sized sets of monomers. Proteins are formed by condensation of twenty types of amino acids. Polynucleotides are formed by condensation of four types of nucleotides. Cellulose, the most abundant polymer in the biosphere, is formed by condensation of one type of monomer – glucose.

For all biopolymer types the net reaction for synthesis is dehydration/condensation. Monomers are covalently linked together by removal of water.

Since they are made by removal of water, all biopolymers are broken down by hydrolysis, which is the addition of water. All biopolymers spontaneously hydrolyze in the aqueous media of a cell. Fortunately, rates of hydrolysis are slow.

Biopolymers are ephemeral. In aqueous soluion, degradation of biopolymers to monomers is always favored in the thermodynamic sense. Any protein, DNA, RNA or carbohydrate, left in the ocean (for example) for sufficient time, will inexorably hydrolyze to monomers. Hydrolysis is partly why dinosaur fossils do not contain DNA. After 60 million years, all dinosaur DNA is completely hydrolyzed. Protein hydrolyzes more slowly than DNA, and small fragments of dinosaur proteins have been recovered.

Why does biology require polymers? Won't monomers (i.e., small molecules) do? No. Biopolymers have unique properties because of their unique molecular interactions. They spontaneously fold and assemble into precise and highly elaborate structures to form enzymes, fibers, containers, motors, pores, pumps, and gated channels, and ribbons of information.

Emergence. The elaborate structures that build biology are emergent upon polymerization. Monomers cannot assemble into the elaborate structures that come easily to polymers. Monomeric guanosine and cytosine do not form base pairs in water. Monomeric nucleosides cannot form informational molecules (like DNA or RNA). Monomeric amino acids do not assemble into hydrophobic cores with hydrophilic surfaces and sophisticated catalytic sites (like proteins). Monomeric glucose does not form robust fibers (like cellulose).

Why? What is so special about biopolymers?

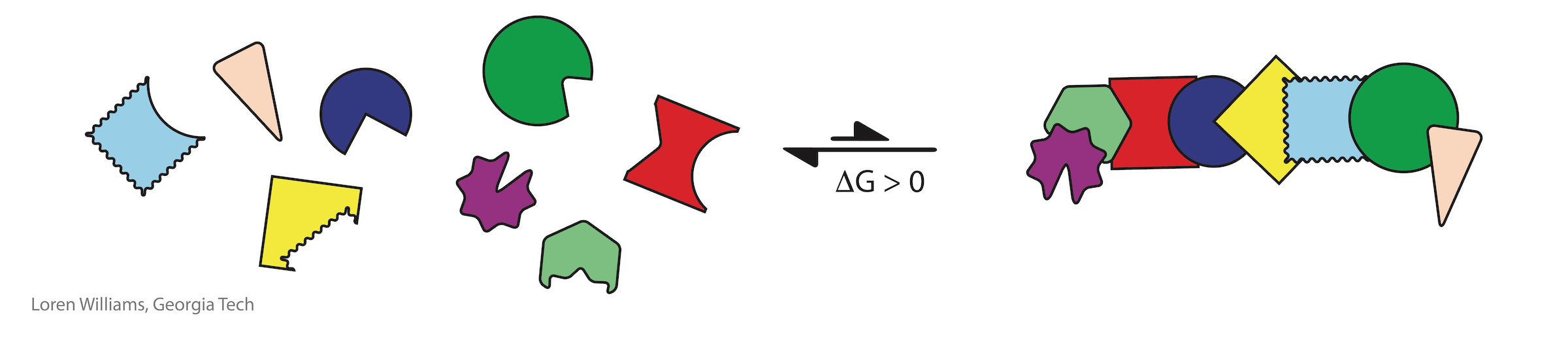

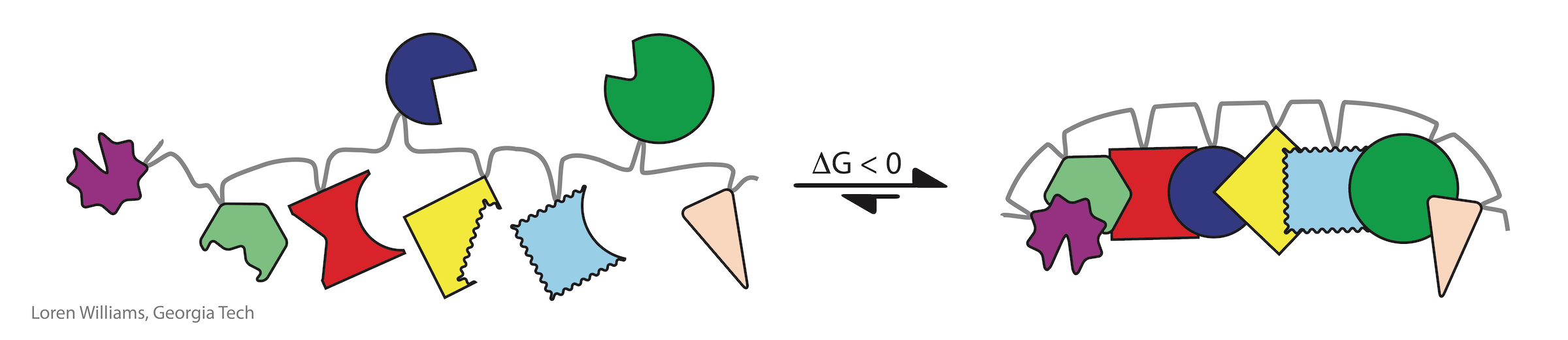

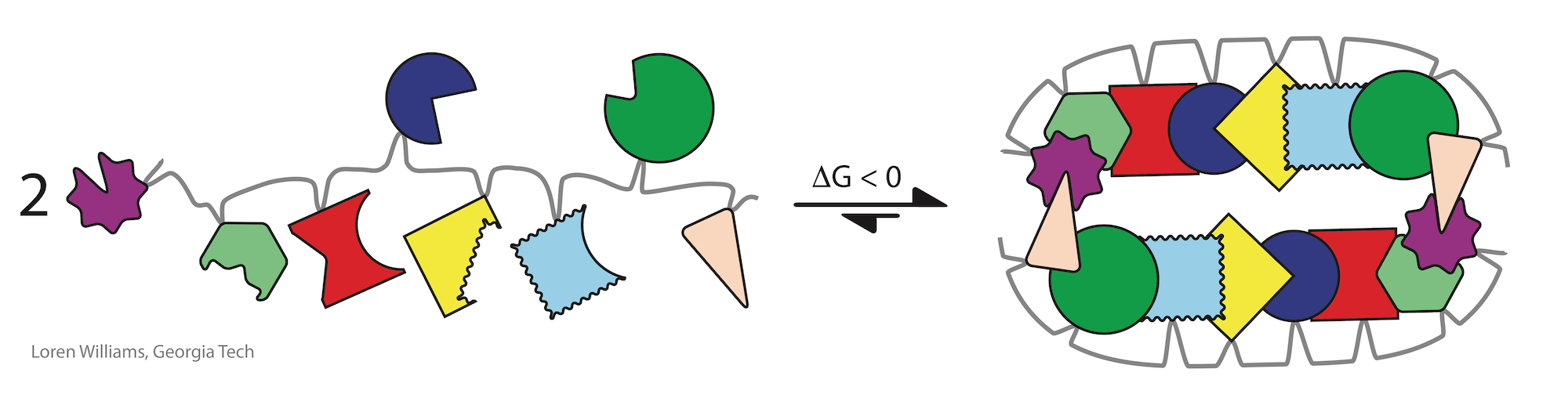

For small molecules (monomers), elaborate assembly is always opposed by a large unfavorable entropy (and therefore unfavorable free energy). The entropy of assembly of a complex mixture into a specific assembly is always large and positive (i.e., unfavorable, making the free energy of assembly large and positive). The more complex the mixture, the greater the entropic penalty of assembly. There are many more accessible states of disassembly or incorrect assembly than of correct assembly. The greater the number of accessible states, the greater the entropy. With a severe entropic penalty for assembly, small molecules simply cannot achieve the elaborate arrangements of functional groups that come naturally to biopolymers.

The entropic penalty for folding of a biopolymer is much less than the entropic penalty of assembly of the corresponding unlinked monomers. Most states of disassembly or incorrect assembly become inaccessible upon polymerization. Therfore, biology's elaborate structures with precisely positioned functional groups are emergent upon polymerization.

Investments of free energy are decoupled in time and space from processes of folding. The free energy of synthesis and polymerization, primarily in the form of ATP and GTP hydrolysis and long term evolution, is invested separately, prior to folding. Proteins can spontaneously fold (i.e., the free energy of folding is negative) only because energy was invested in selecting appropriate sequences and in polymerizing monomers of those sequences.

It is easy to assemble a jig saw puzzle if the pieces are correctly linked by the right short springs.

When Arthur C. Clark wrote, "Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.", he could (should) have been writing about assemblies in biochemical systems.

Biological assemblies are indistinguishable from magic.

They are not magic, but we have very little understanding of their ultimate evolutionary origins, and so they appear to be magic.

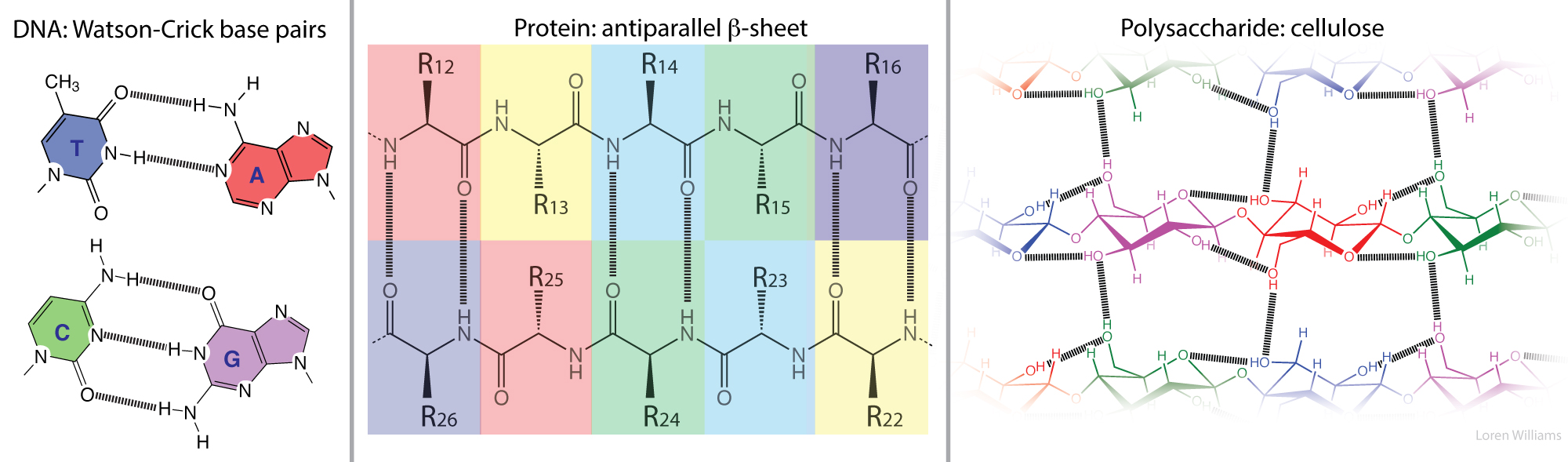

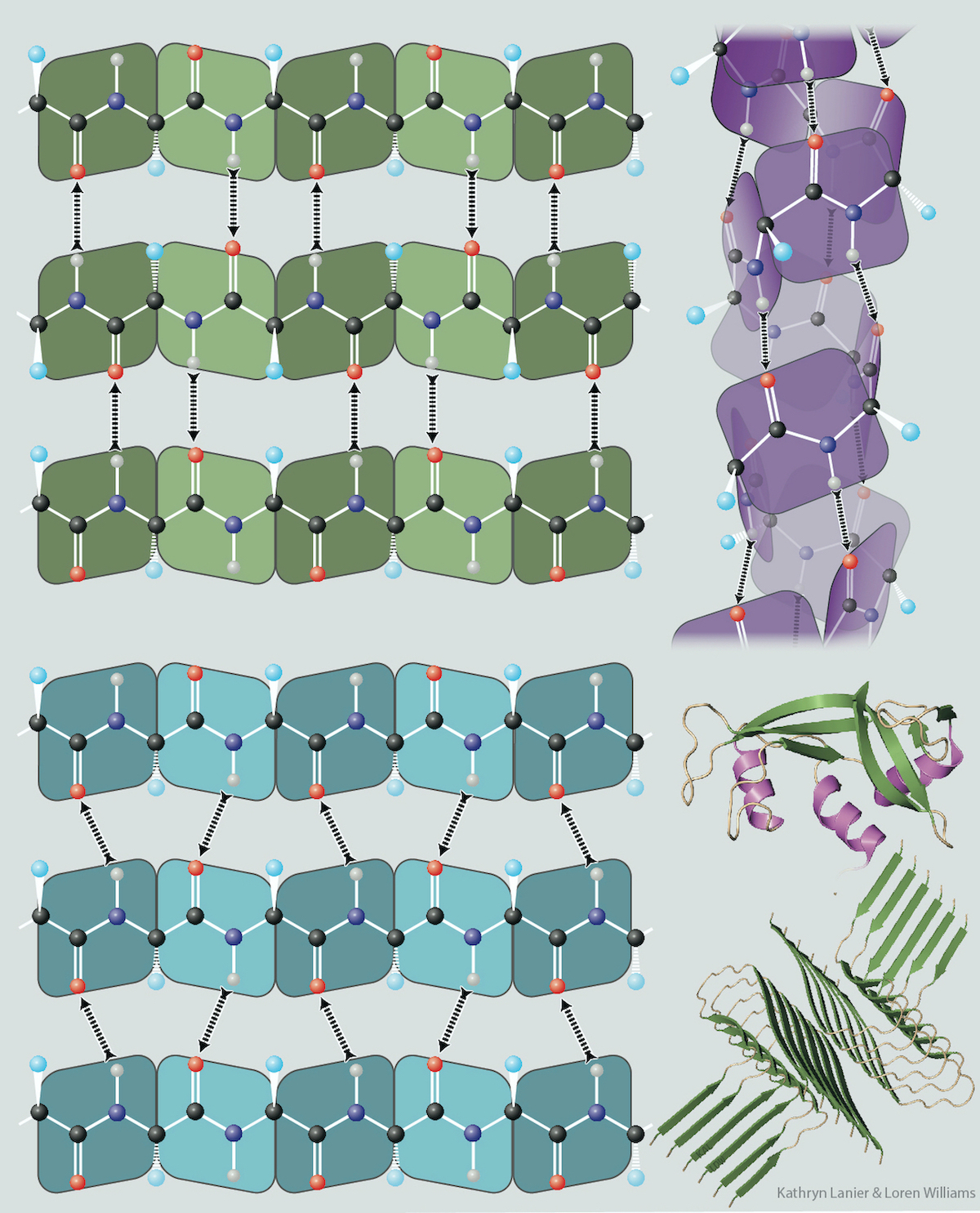

Self-complementarity is a universal property of biopolymers. Self-complementarity is proficiency for preferential self-binding, which is the ability to attract and associate with self to the exclusion of non-self. Self-complementarity is important in protein folding, RNA folding, DNA annealing, and assembly of cellulose fibers.

Three-dimensional structures of folded/assembled DNA, RNA, protein, and polysaccharide reveal extensive networks of highly specific molecular interactions in which biopolymers complement themselves. Hydrogen bonding donors complement acceptors in 2D and 3D arrays, sometimes over vast surfaces. The locations and directions of the donors and the acceptors are matched.

The term “self-complementary” has traditionally referred only to the interactions between nucleic acid bases, such as those in the DNA duplexes.

“Self-complementary” is not commonly used to describe the polypeptide backbone or cellulose, because the nomenclature for molecular interactions of nucleic acids is historically distinct and separate from that describing interactions of proteins. However, “self-complementary” is an exact and accurate description of the polypeptide and polysacharide backbones. Both of these biopolymers selectively adhere to themsleves via extended arrays of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors that are geometrically matched in three-dimensional space. For protein, this donor/acceptor matching is realized by local interactions within α-helices, or by non-local interactions within β-sheets.

Preorganization makes import contributions to self-complementarity. Biopolymers are massively preorganized, meaning the actual entropic cost of folding and assembly has been paid during biopolymer synthesis, and during billions of years of evolution, and does not have to be accounted for during folding or assembly. At high temperature or in chemical denaturants biopolymers retain a kinetic propensity to fold. Folding is fast and spontaneous when the temperature is lowered or the denaturant is removed.

Biopolymers are intrinsically pre-organized for folding and assembly. Pre-organization of protein, DNA, RNA and cellulose can be parsed in the following ways:

Because of their directionality, tunability, and ubiquity in simple organic molecules and biological polymers, hydrogen bonding interactions are one of nature's most powerful devices of self-complementarity. However, not all self-complementary surfaces in biology involve hydrogen bonds. Leucine zippers, between α-helices, are examples of self-complementary interactions that involve molecular interactions other than hydrogen bonds.

Mutualisms are everywhere in the biosphere and are fundamentally important in evolution, ecology and economy. A mutualism is a persistent and intimate interaction that benefits multiple interactors. Mutualisms involve proficiency exchange, interdependence, and co-evolution. Mutualisms traditionally have been described at levels of cells, organisms, ecosystems, and even in societies and economies. Eukaryotic cells, with mitochondria and nuclei, are a culmination mutualism between simpler prokaryotic cells. Essentially every species on Earth is involved in mutualisms.

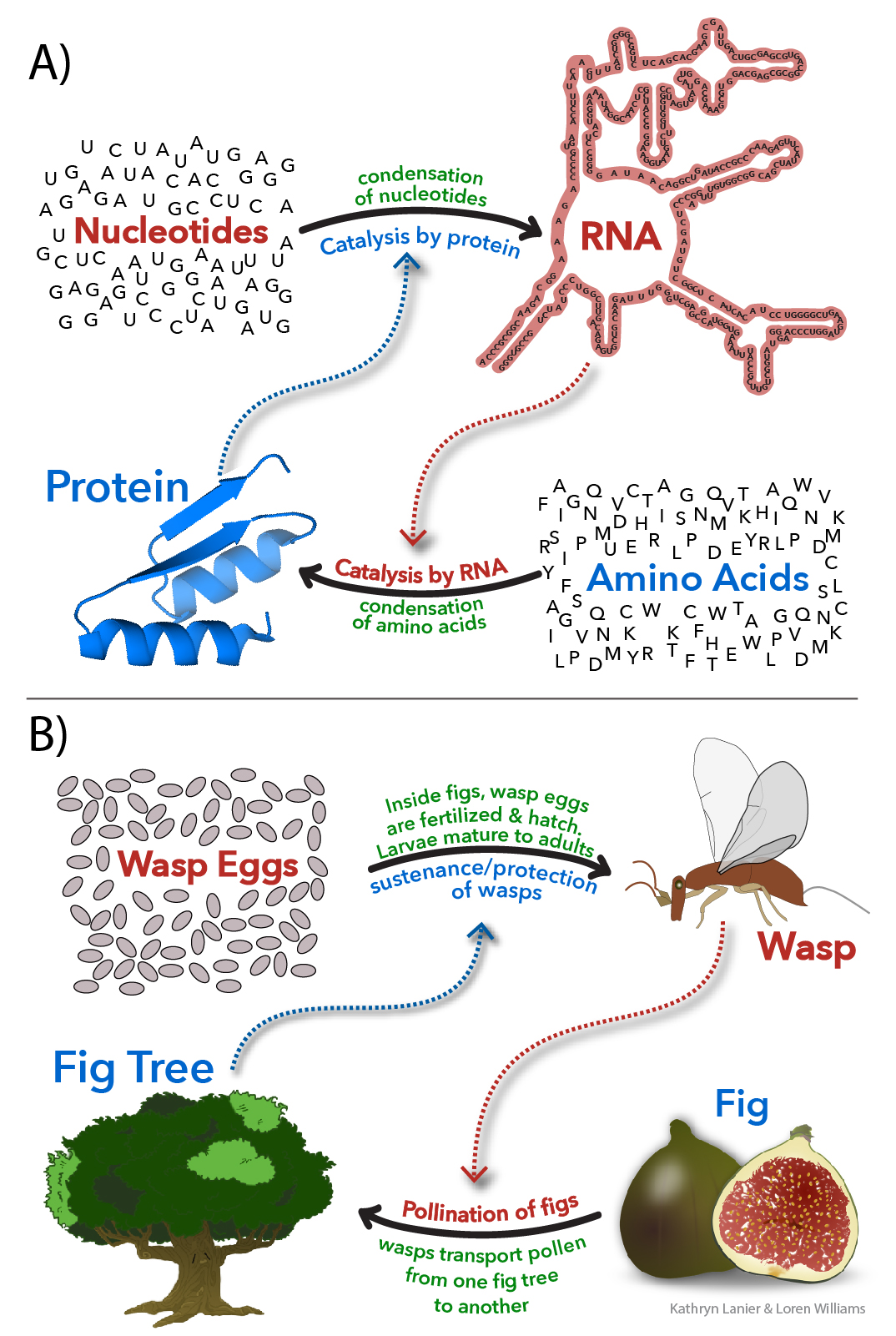

Molecules. Molecules can form mutualism relationships. Biopolymers satisfy all of the formalisms of mutualism, and it is useful to apply those formalisms to understand them. Biopolymers synthesize each other and protect each other from chemical degradation. Protein synthesizes RNA (polymerases) and RNA synthesizes protein (ribosome). During the essential steps of translatioin process, coding is performed by proteins (aaRS enzymes that charge tRNAs), while decoding is carried out by RNA (mRNA and rRNA) in the ribosome.

Molecules in Mutualism describes and explains: (i) survival – extant biopolymers are more persistent than competing polymer types, which are now extinct; (ii) fitness – biopolymers are more ‘fit’ in combination than in isolation; (iii) distance – each biopolymer type has distinct proficiencies and chemical characteristics; (vi) innovation – proficiencies of one type of biopolymer release constraints on partner biopolymer types; (v) robustness – biopolymer types have been fixed for billions of years, meaning biopolymers compose the seminal and most ancient mutualism in the biological world; (vi) co-evolution – biopolymers co-evolved and created each other in an emergent environment; and (vii) parasitism – amyloids and phase separated RNA gels appear to be examples of direct self-interest and escape from mutualism.

It is useful to think of a cell is a consortium of molecules in which nucleic acids, proteins, polysaccharides, phospholipids, and other molecules form a broad mutualism that drives metabolism and replication. Analogies are found in systems such as stromatolites, which are large consortia of symbiotic organisms.

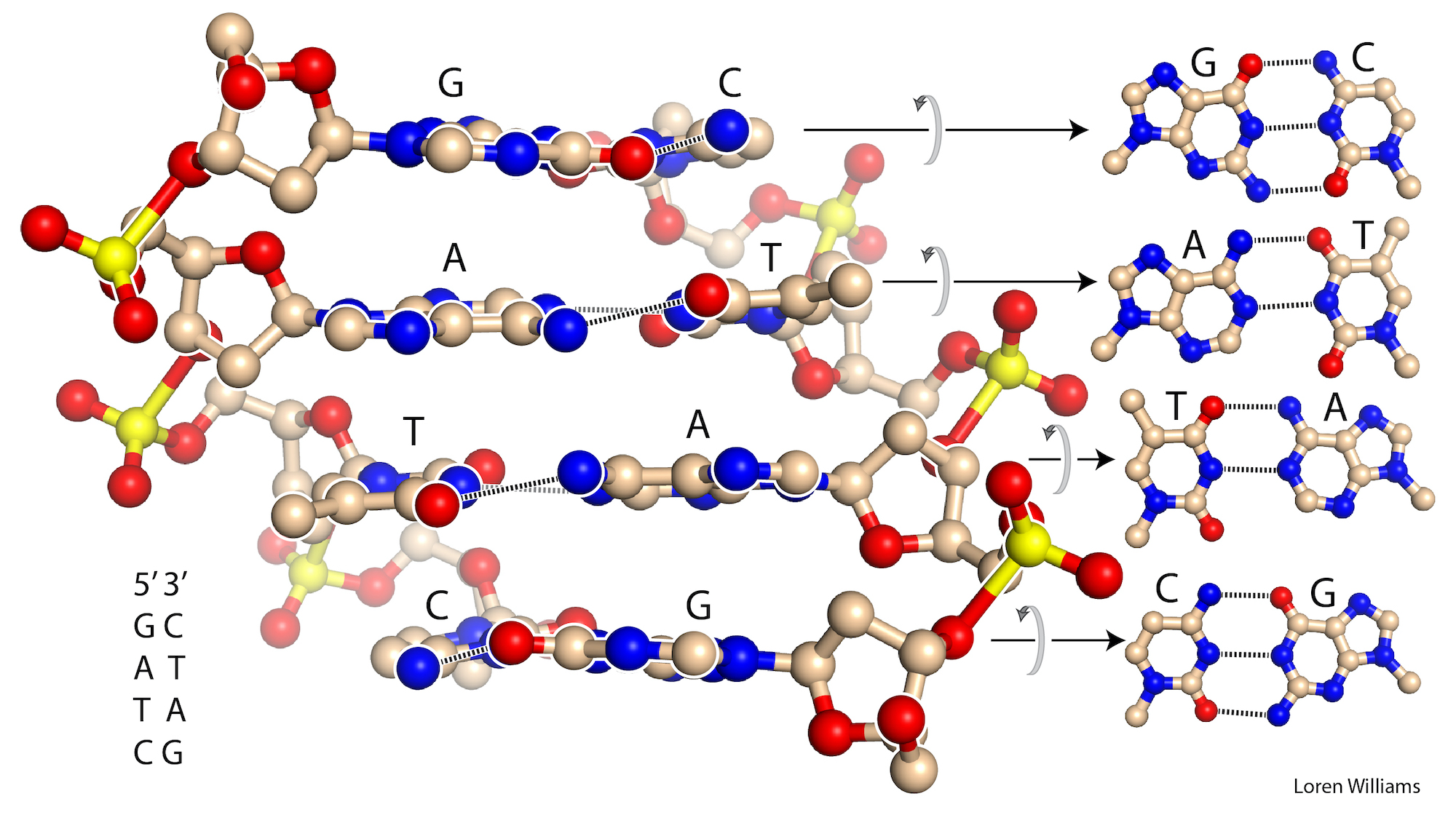

O. Base stacking and base pairing.

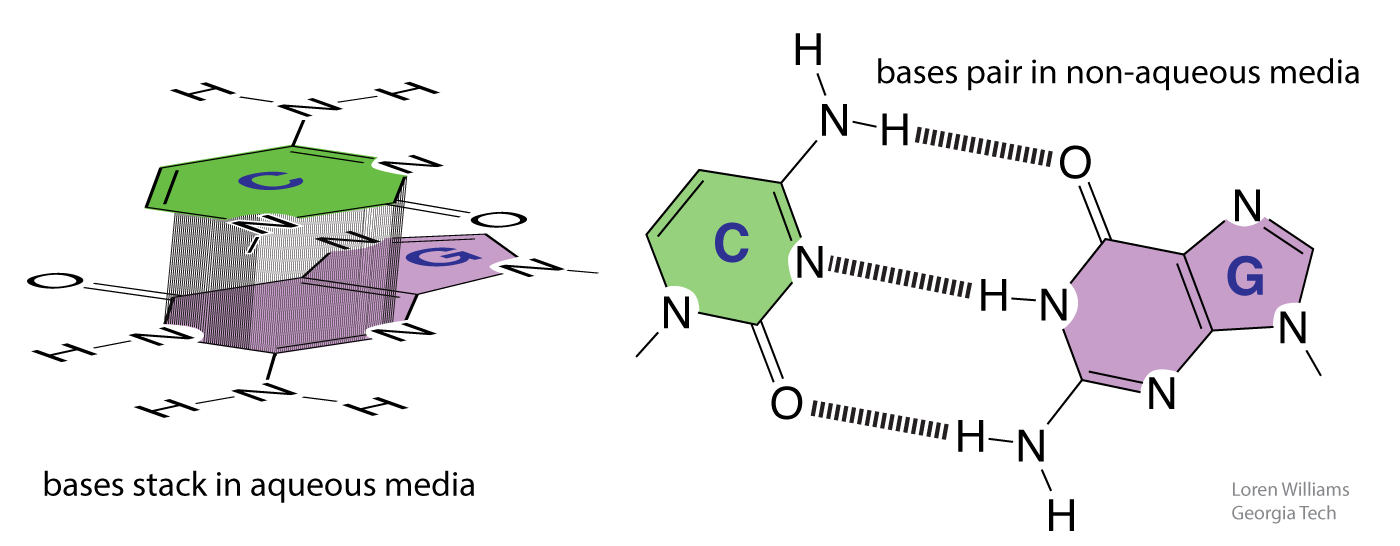

Base-base stacking is the dominant stablizing interaction in double-stranded DNA and RNA and in complex RNAs like tRNA or rRNA. Please do not attribute stability of DNA to base-base hydrogen bonding. When base-base hydrogen bonds are disrupted, they are replaced by base-water hydrogen bonds. It's a wash.

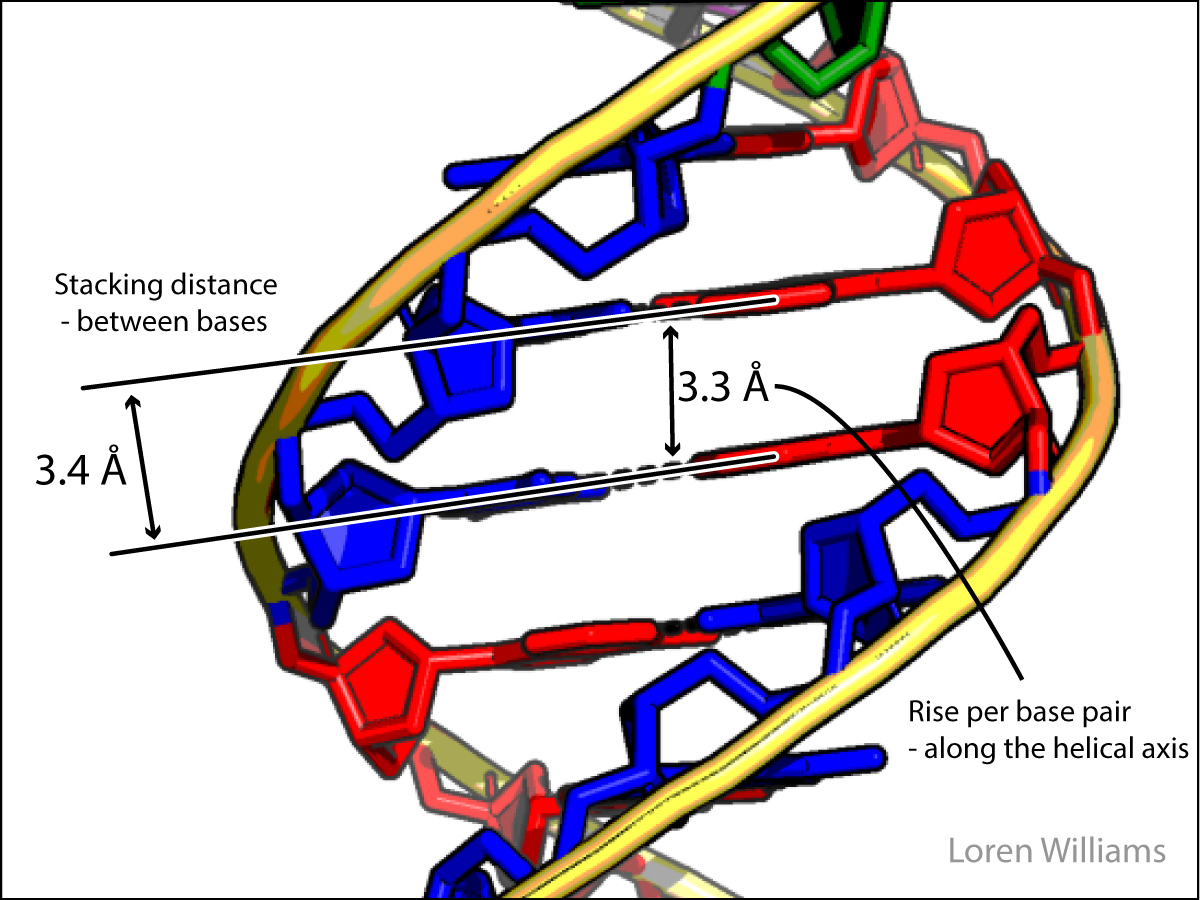

In both DNA and RNA duplexes, the distance between stacked base pairs is 3.4 Å, the minimum allowed by short range repulsion. In a B-form helix (DNA), base pairs are slightly inclined; Base pair normals are not exactly parallel to the helical axis. Therefore, the rise per base pair along the helical axis is slightly less than the stacking distance of 3.4 Å. In an A-form helix (RNA), the inclination is greater and therefore the rise per base pair is less (2.3 Å).

What is base-stacking? Base stacking is complicated and involves many types of molecular interactions. London dispersion is a primary stabilizing force in base stacking. Dipole-dipole, dipole-induced dipole, and dipole-quadruple interactions are also important. An additonal type of interaction, called Charge Penetration, makes important contributions to base stacking. Charge Penetration arises at short range, when the Π-cloud of one base interacts favorably with the nuclear charges of an adjacent base.

The hydrophobic effect contributes to base stacking. Mono-nucleosides spontaneously stack in water. However, they do not form base pairs because water-base hydrogen bonds complete effectively with base-base hydrogen bonds.

Mono-nucleosides spontaneously pair in non-aqueous solvents such as CH2Cl2. Non-aqueous solvents do not compete for hydrogen bonding with the bases. There is no hydrophobic effect to drive stacking and the bases of mono-nucleosides do not stack in non-aqueous solvents.

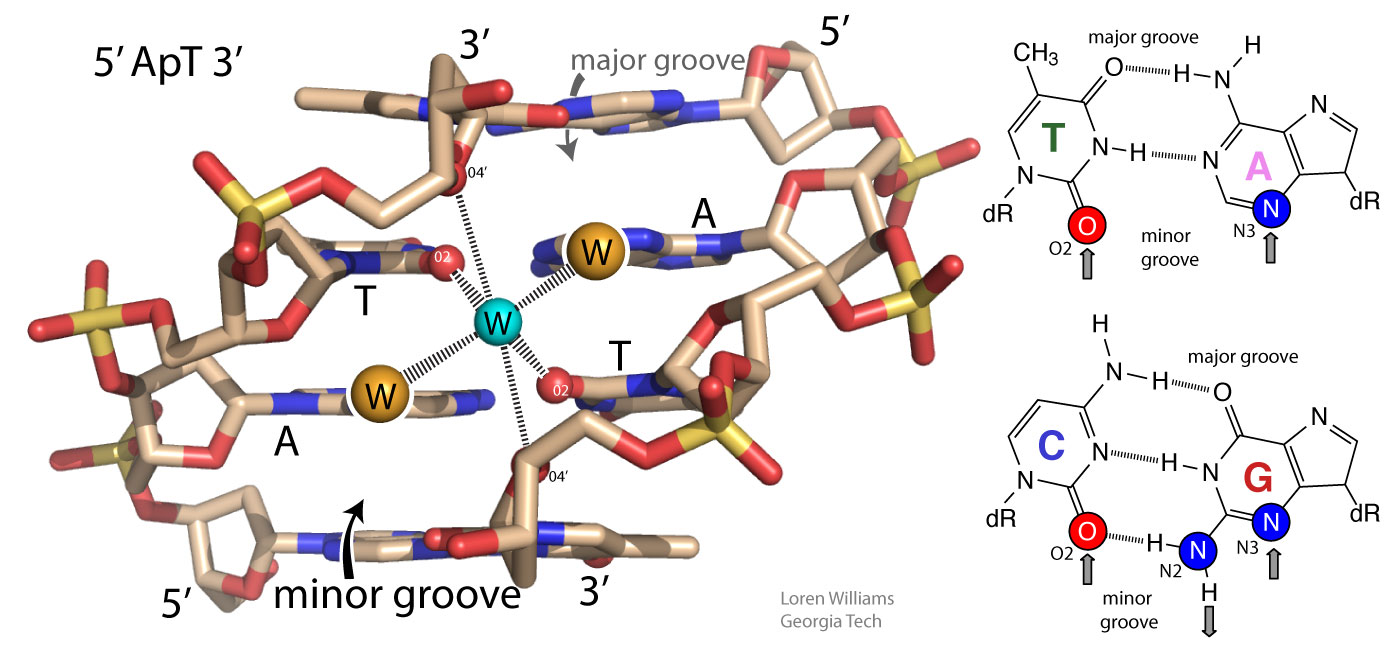

GC base pairs are more stable that AT(U) base pairs; GC-rich duplexes have higher melting temperatures than AT(U)-rich duplexes. But why? It is commonly stated and written, in textbooks and all over the web, that this difference can be understood by counting Watson-Crick hydrogen bonds (GC>AT). Not true. As noted above, when you break base-base hydrogen bonds you form base-water hydrogen bonds. So hydrogen bonding does not contribute much to the net stability of DNA or to the differential stability of GC-rich over AT-rich DNA. A greater number of base-base hydrogen bonds is not the reason for the greater stability of GC-rich DNA

In fact, AT base pairs are less stable than GC base pairs because AT base pairs, in the minor groove, cause ordering of water molecules, which is destabilizing. Low entropy water molecules are released when AT base pairs are melted. The greater stability of GC-rich DNA compared to AT-rich DNA is caused by differences in hydration, not by differences in base-base hydrogen bonds. You can read more about this in Privalov, NAR, 2015, 43, 8577 and can access a pymol script showing water molecules in an A-tract minor groove here.

A source of confusion. Electrostatic forces are between charged species and are unimportant in base stacking; bases are neutral. Confusion arises because high level theory papers use a different parsing scheme for molecular interactions, and allocate some interactions between neutral species into the electrostatic category. Unless you do quantum mechanics for a living and don't care if others can understand you, it is best to refrain from using the term 'electrostatics' to describe interactions between net neutral species.

P. Template-directed catalysis.

Biological systems have unique abilities to link complex molecular interactions to catalytic functions. Sophisticated non-covalent interactions control formation of covalent bonds. Some of the most advanced forms of these phenomena are observed in DNA and RNA polymerases, and in the ribosome. In these systems hydrogen bonding and other molecular interactions direct catalytic function. In an RNA polymerase, if 'correct' hydrogen bonding (i.e., C-G or A-U/T Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding) occurs between the template strand and the incoming nucleotide, then the enzyme catalyzes formation of a covalent bond. When 'wrong' interactions (e.g., a G-U pair) are detected, the enzyme kicks out the incoming nucleotide without forming the covalent bond. Therefore one molecule acts as a template that directs synthesis of another molecule, in close analogy with the way that a pastry template directs the shape of the pastry.

(i) Biology is molecules in mutualism. RNA makes protein. Protein makes RNA. A cell is a consortium of molecules in mutualism relationships.

(ii) Biology is layered emergence. The properties of water are emergent on condensation. Properties of amino acids, nucleotides or sugars are emergent on polymerization.

(iii) Biological assemblies are indistinguishable from magic. The evolutionary processes that produced the backbones of biological polymers appear lost in time.

This document is dedicated to the memory of the late Professor Charles Lochmuller (right) of Duke University. Dr. Lochmuller was a good guy, a natural comic, and an eminent scientist.

Here I approach biochemistry in a new (I believe) way. It is tradition, starting with Lehninger's first Biochemistry textbook and continuing in essentially all subsequent biochemistry textbooks, to teach about each type of biopolymer in isolation of the others other. Protein DNA, RNA and carbohydrate are described in distinct, well-separated chapters as unrelated chemical phenomena.

In Part 2 of this document I present DNA, RNA, polypeptide, and polysaccharide in the context of their common attributes. Rather than focusing exclusively on the differences (amino acid side chains, nucleic acid bases, etc), I focus on the profound universal properties (self-complementarity, emergence, etc) that unite biopolymers. In my view only by learning about biopolymers in context of each other can one hope to achieve a reasonable understanding of them.

I was fortunate to learn molecular interactions from Dr. Lochmuller in his separations class. I have extended Dr. Lochmuller's parsing scheme to include cation-Π, etc. Some of the source material for Part 1 of document is my 1984 Ph.D. thesis. I wrote core elements in around 1990-92, and expand, revise and clarify the figures and text when inspiration strikes and time is available. The document has benefitted from many discussions with Professor Nicholas Hud. I created this resource and continue to improve it based on my beliefs that:

The development of this document has been supported by the NASA Astrobiology Institute, the National Science Foundation and the School of Chemistry and Biochemistry at Georgia Tech, all of whom have supported my research laboratory and my public outreach efforts. Comments and suggestions for improvements are welcome and should be addressed to ldw@gatech.edu. I am hopeful that students, especially those who lack resources for textbooks, find this site to be useful.

Reuse. The images and text here can be reused with attribution for noncommercial purposes.

Sincerely,

Loren Williams,

Professor

Georgia Tech